The Ptarmigan Traverse

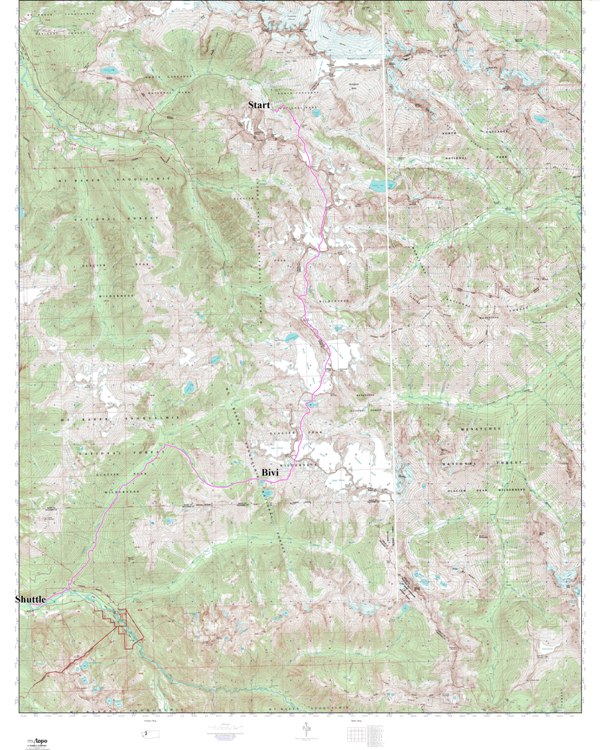

Scott scrambles up to Cache Col and drops his pack besides mine. We’ve been moving just over two hours since the trailhead and have stopped to get our first glimpse at the route before us. Our goal is the Ptarmigan Traverse – a 35-mile off-piste, haute route traversing the southern upheaval of the North Cascades.

This terra incognita was first explored in July of 1938 over a period of 13 days. The Ptarmigan Climbing Club made numerous first ascents along the route – an effort that is still recognized as one of the greatest feats in the North Cascades… ever. Their report was never published, and due to tumultuous world events, the traverse wasn’t repeated for 15 years. In September of 1953, Dale Cole, Bob Grant, Mike Hane, Erick Karlsson and Tom Miller reversed the route and published their report in The Mountaineer. It was this second traverse that turned the Ptarmigan Traverse into the classic it is known as today. Miller’s photos were published as a book, The North Cascades (1964), and later submitted as supporting documents in a bill sent to Congress that established the North Cascades as a National Park (1968).

But we are here under a different guise; our goal is to forego the climbing and make a single push of the classic traverse. Success requires we go virtually naked – as minimal as possible. The 10 essentials have been cropped to six. Rope, ice axe, rain jackets… stowed down at the car. No tent, no sleeping bag, no room for error.

Just then Scott coolly asks if I have the key.

“Don’t dine on my dignity… what key, the car key?”

We’ve travelled five miles into our project without the one piece of gear we cannot omit: the key to our shuttle car left at the route’s terminus… it’s safely below locked at the start.

I take a deep breath and consider the options. We started late for such an ambitious goal so I’m somewhat worried that we could be spending a memorable night inside a wind-swept cirque. The decision is easy. We need the key, but tomorrow will require an earlier start, so I take advantage of our foiled attempt and reconnoiter what lies ahead.

“Its much more compact than I thought it would be,” I share with Scott. “I bet we can move between passes in 2-3 hours time.”

We jog down the five-miles to the trailhead, passing Seattleites up for a Sunday stroll.

Take 2

The alarm sounds at a head-pounding 2 a.m. We brew up a quick cup of coffee, grab our packs and eat breakfast on our way back up towards Cascade Pass. The prior day’s ‘training run’ tempered our pace, so we walk most of the now familiar trail.

To save weight, we’ve purposely filled our reservoirs with minimal water, just enough to quench between watering holes. We stop to rehydrate at Kool-Aid Lake (more of an alpine tarn) under the lunar shadows of Magic Mountain. The morning wind claws at our gossamer shells, so we quickly shoulder our packs and round the cirque towards the Red Ledge, an ambiguous rib that deflects an obvious line. After fumbling 30 minutes up a crack, an overhanging chock stone thwarts our effort, forcing us back down to reassess. I notice a ramp to our left that appears to skirt the wall. Just when the goat trail seems to cliff out, the wall eases onto heather-covered hummocks and boulder gardens and we run down towards the Middle Cascade Glacier.

Mount Formidable’s awe-inspiring North Face.

Mount Formidable’s awe-inspiring North Face. Scott soaking up the early light on Formidable’s North Face.

Scott soaking up the early light on Formidable’s North Face. Scott traversing solid ground before we step onto the bulletproof Middle Cascade Glacier.

Scott traversing solid ground before we step onto the bulletproof Middle Cascade Glacier.The early morning ice is impervious to our underwhelming crampons. To strike a balance between effective and lightweight, we brought running crampons that strap over our trail runners. But the reality is they are probably better suited for Pebble Beach than the Middle Cascade; as we step onto the ice they nearly skitter across the glacier’s bulletproof surface. Using trekking poles to self-belay, we gingerly pick a line through the icefall’s broken surface. Below the Spider-Formidable Col, we scramble up the yawning gap between rock and ice then boot-ski down the softer, southern-exposed slopes towards Yang Yang Lakes.

I take a look at the map while Scott refills our reservoirs. My notes share that the route should skirt below the rocky buttress to our right, but the map seems to yield a weakness in its fortress-like wall. We climb around talus slopes and up what appears to be a dead-ending couloir, forcing us to step onto the buttress.

We eventually ease out onto a bench and deduce that our detour likely cut an hour off our time and positions us favorably on the Le Conte Glacier. Below, a labyrinth of crevasses folds over the glacier’s surface. Shirking exposure, we quickly skirt under Le Conte’s ridgeline towards Sentinel Peak. As the sun warms the glacier, the once firm surface has turned to granulated sugar smeared atop lacquered ice – once again reminding us of our poor choice of crampons. We trade leads kicking steps in our running shoes until bruised toes force the swap.

A close up view of Le Conte, Sentinel and Old Guard peaks.

A close up view of Le Conte, Sentinel and Old Guard peaks. Scott scurries across the Le Conte Glacier under Le Conte Peak.

Scott scurries across the Le Conte Glacier under Le Conte Peak. The author traverses the Le Conte Glacier.

The author traverses the Le Conte Glacier.

We scurry across angled scree fields and over the snout of the South Cascade Glacier, after which a quick climb up the ramp below Lizard Mountain reveals the jaw-dropping Dana-Chickaman Glaciers. Wispy, silver waterfalls pour off the hanging glaciers, clinging to the granite spires of Dome Peak and Spire Point. Below us, White Rock Lakes shimmer like Cascadian jewels, reflecting the Valhalla-like cirque. We boot ski a 100-foot black diamond down to the lakes and take a much-needed rest, rehydrate and binge on the ambrosial landscape.

Scott hints that the day’s effort is taking its toll and suggests bivvying at the lakes. While beautiful beyond words, the high, exposed, and windswept area would make for a miserable bivy with our limited supplies. I supportively suggest that two more hours will bring us to the end of the glaciers and another two hours will drop us below tree line, where we can find a more suitable spot.

The view from just below Lizard Mountain into the impressive Dana-Chickaman cirque.

The view from just below Lizard Mountain into the impressive Dana-Chickaman cirque. The majestic Dome Peak.

The majestic Dome Peak. Binging on the view from White Rock Lakes.

Binging on the view from White Rock Lakes. The hills are alive.

The hills are alive.We round Dana Glacier and make our last snow climb towards Spire Point. Nearly to the minute, two hours later, we find ourselves at the col looking down to Itswoot and Cub Lakes and the verdant forest below. Exhausted, we consciously resist the urge to follow the fall line down the snowfield to our right, which cliff out according to our maps. Instead, we painfully down-climb loose scree along Itswoot’s rocky ridge, cautiously descending into the valley.

As the sun drops behind the shouldering ridge, we walk into Cub Lake’s protected cove. With water, shield from wind and a picture-framed view of Glacier Peak, we decide to call it and walk out at first light. We pull on our extra clothing – cycling sleeves, lightweight tights, wind jackets, wool caps, gloves, and a down vest each – and crawl into our mylar sacks for a fitful night of restless legs and awkward spooning.

Scott descends down Itswoot Ridge to safer ground.

Scott descends down Itswoot Ridge to safer ground. The author hops over fresh glacial runoff before Cub Lake.

The author hops over fresh glacial runoff before Cub Lake.

The author navigates through a rats nest of debris covering the Bachelor Creek Trail.

The author navigates through a rats nest of debris covering the Bachelor Creek Trail.

Wet, clammy, and shivering, I make the first move to worm out of my bivi sack; Scott quickly follows suit. We shove our wet gear into the packs and make the last hump upwards over the ridge then its down, down, down into the lush Bachelor Creek drainage. Thick with devils club, salmonberry and alder slide, the descent constantly pulls at our attention. Recent avalanches have piled forest wreckage over the creek forcing us to climb over, in and out of downed timber. Eventually the debris abates and a trail trickles out from under. We parallel to the creek until it joins Downey Creek, which eventually drains into the Suiattle River. A washout and a bridge out, we walk the 8.5 miles from the trailhead to our car, mumbling nonsensical gibberish about seasonal blueberry milkshakes.