The Maestro

Raúl Revilla Quiroz left a mark on the Mexican climbing community by following his passion. Respected and admired throughout the country, he was inducted into the Alpinism Hall of Fame of the Mexican Sports Confederation in 2009 in recognition of his vertical accomplishments. His sudden death in January 2022 was a surprise, and we at Patagonia will always remember him. The following words are a tribute to his summits, his work as a skilled climbing shoemaker and his legacy as a mentor and passionate promoter of climbing.

Friends and family remember Raúl Revilla Quiroz’s legacy.

“Only those who have felt the thrill of taking a step to the void 100 feet over the ground, who has drunk water after working on the rocks for seven hours nonstop, who has enjoyed a soft and warm bed after two or three cold nights on the open field, who has felt the affection of loved ones coming back home, who has understood the invisible bond of love and comprehension with the rest of the team, the enormous pleasure of eating after a whole day without taking a bite for being too busy climbing a rock; only those can understand rock climbing and the love for the mountain.” —Tomás Velázquez, Mexican Climber’s Guide, 1955.

Raúl Revilla Quiroz—the man behind legendary Revilla boots and one of the most prominent big-wall climbers in Hidalgo, Mexico, during the ’40s and ’50s—was one of those people you admire not just for what they did but also for who they were. A passionate climber, craftsman and, above all, mentor for generations of Mexican climbers and mountaineers, Raúl was rightly given the nickname “El Maestro.” He left behind a remarkable collection of routes and a variety of inventions that paved the way for the development of climbing in Mexico.

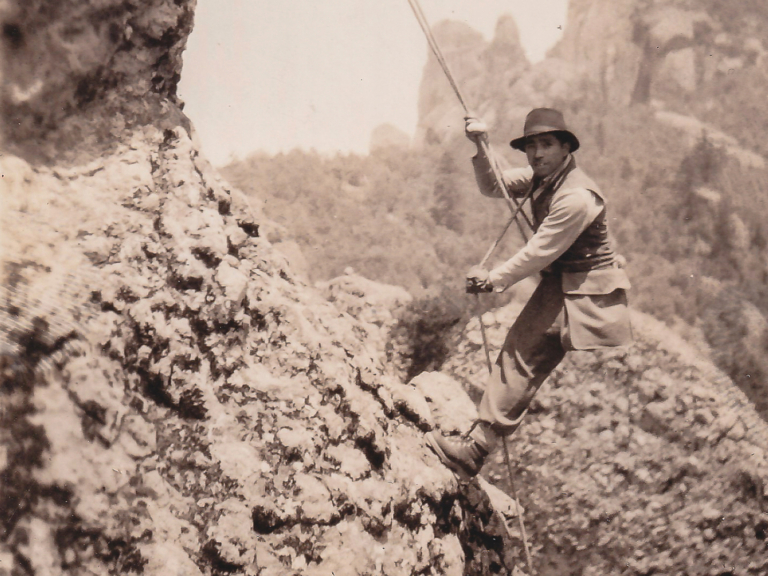

Raúl reaches a summit in Hidalgo in the ’40s or ’50s, the golden age of Mexican first ascents —of which he was a lead character. Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mexico. Photo: Alfredo Revilla Collection

Born on January 23, 1923, in Pachuca in the state of Hidalgo, Raúl’s early years forged his personality. In the absence of his parents, a very young Raúl was raised by a close friend of his mother’s, Doña Aurelia, as her own. Together they overcame difficulties like a typhoid epidemic—which Raúl miraculously survived on a diet of one cracker and two swallows of milk a day—and poverty, which is why he started work at the age of 9 at the Ten-Pac factory, a shoe repair shop that specialized in heavy-duty work boots worn by miners. There, he mastered the skills that would later help him develop his most famous creation: leather climbing boots with soles made of recycled airplane tires, which have accompanied ascents in the Mexican mountains for over six decades.

The rocky landscapes that surrounded Raúl’s hometown stirred his interest in exploration, an activity that would later become a pact with nature and establish his career as a climber. His love for those wild places and their summits is mirrored in the prologue he wrote for V Grado by Raymundo Solís: “Visiting the mountains you will find natural treasures you must protect from the plague of civilization: lakes, beautiful, steep cliffs, vast meadows, and deep couloirs full of trees, streams, and oxygen that revives the desire to live and the longing for calm.”

Raúl’s relationship with climbing began somewhat formally in the late 1930s when, as a teenager, he was invited by members of the Exploration Club of Mexico to climb El Fistol del Diablo in Las Ventanas. Climber and mountaineering guide Héctor Ponce de León reminisced on those excursions with Raúl. “I remember those eyebolts they used in the walls,” he says. “The classic route of Las Ventanas [originally had] just one nail protecting 25 meters of climbing, a nail from which I wouldn’t hang a picture today. I knew that gear had been developed among others, but mainly by Revilla. I was fascinated by the stories about climbing before open-gate carabiners existed, when they’d have to fix a nail in, untie themselves, pass the rope through the ring and tie again … I can’t picture myself on a wall doing that, untying and then tying in again!”

Not long after that, Raúl climbed Peñón del Zorro with Antonio Ortiz, José Gertrudis Menchaca and Francisco Santamaría, an ascent for which they used a stick as a rung for the first move. Fifteen meters above the first anchor and 45 meters to the ground, they jammed a thin trunk into the crack for lack of pitons or nails. After reaching the summit, they rappelled down with their bare hands on agave ropes.

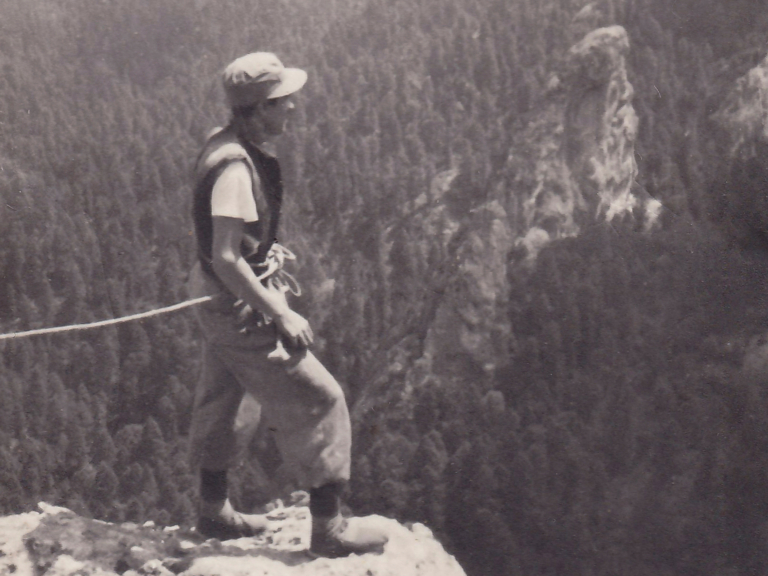

There is always a bit of anxiety when rappelling a big wall. Imagine doing it without a harness or a belay device! Raúl gets down to earth the old-fashioned way after a day of climbing in Pachuca. Photo: Alfredo Revilla Collection

Raúl quickly paved the way for the future of the sport in Mexico, climbing with minimal equipment: the north wall of Las Ventanas, El Centinela, La Blanca, Los Panales, El León Alado, Las Tres Marías, La Aguja de las Monjitas, El Corazón, El Circo del Crestón, La Pezuña and La Muela. In 1942, with José Gertrudis, Antonio and Francisco, Raúl became infatuated with the famous Peña Rayada, a route that marked a new era in Mexican climbing. Using no protection and with just a rope, he led every pitch because, as he recalled, “My partners had families and I didn’t yet.”

There’s no exact data on the number of first ascents by Raúl, but there’s certainly more than we think. And although he is largely remembered for the footwear and climbing gear he developed as part of his mountain climbing philosophy, what he left behind goes much further. In the words of Germán Wing—one of Mexico’s greatest climbers who was strongly supported by Raúl—his legacy should not be interpreted as something material, like a mountain, a route or some nails. “What you leave as a legacy is the spirit, the essence of your philosophy, of your way of thinking,” Germán says of Raúl, whom he admired as a seasoned, intelligent and visionary craftsman and adventurer.

Raúl (left) and Emilio Vega (right) stand at the top of a route with a third unknown climber after a successful day of climbing. Photo: Alfredo Revilla Collection

Raúl’s prologue in V Grado distills the philosophy he lived by: “By climbing cliffs, walking over fallen trees and exploring uncharted areas, your body will regain its ability to enjoy, like a child, the simplest things of life,” he writes. “Steps over the mountain will allow your mind to feel the magnificence of the creator, and your body will become addicted to the euphoria produced by healthy physical exercise …. Never lose your love for nature or the fear of this unique sport. Disregarding the mountain means losing everything.”

To make the best possible mountaineering boots, you need to know the terrain and the conditions they will be exposed to. Raúl Revilla and Emilio Vega on one of the many volcano ascents that provided the knowledge he’d use to stand out in his later work as a shoemaker. Mexico. Alfredo Revilla Collection

Back then, climbing was all about making first ascents. Any untouched wall or summit stirred up the climbing community’s enthusiasm, and they threw themselves at new challenges without any guidance or beta. Those were also life-or-death climbs. Reaching the summit was an obligation, and climbers would use any prop at hand: espadrilles and Ten-Pac boots for climbing shoes; railroad spikes and agave ropes tied with a bowline to their hips for safety; early techniques such as the Dülfersitz rappel; and leather jackets to help avoid abrasion. “Raúl Revilla represents that romantic era in alpinism,” says Héctor Ponce de León, “not only in Mexico but in the whole world …. That time when relevant conquests were reached in mountains and walls. What distinguished him the most was the spirit of adventure, that climbing by then represented more than a sport, it was an ideal … an exploration of mental and physical possibilities.”

There was no climbing equipment in Mexico in the early years of Raúl’s climbing career, so everyone developed their own solutions. His innovative mind and skillful hands made him a prolific designer and engineer of climbing gear. Seven decades ago, he first worked with a blacksmith to create pitons, pegs and, taking an idea from First on the Rope by Roger Frison-Roche, his first bent-wire carabiner with a train rail, which he adapted into a wire gate. From then on, it was no longer necessary to risk one’s life by untying the rope from the waist to lead.

On April 7, 1952, Raúl made the first attempt on the west face of Las Brujas with Emilio Vega, his climbing partner. The route still sees very few ascents due to its demanding finish with an unprotected runout. Raúl and Emilio had to bail just 20 meters from the top. A week later at the age of 27, Raúl married Paula Sandoval Arroyo, whom he met at the Ten-Pac factory; she was terribly afraid of losing him on a dangerous climb. After making a wedding promise to her to quit climbing, Raúl passed all his gear on to his apprentice, Juan Medina Saldaña. A little less than a year later, Medina freed Las Brujas.

Much like today, in the 1940s community was an essential part of the development of climbing. Raúl and his climbing partner, Emilio, pose with a group of friends in the mountains. Photo: Emilio Vega Collection

Though he had agreed to quit climbing, Raúl stayed close to his passion, fostering the sport whenever he had the opportunity. By the early 1960s, he became the first shoemaker to offer solid, waterproof shoes that could handle use on tough climbs. He dedicated nights and days to developing his famous Revilla boots, climbing shoes and, for some time, packs and sleeping bags. The Revilla reputation took off at the end of that decade, when the best Mexican speleologist of the time, Jorge de Urquijo Tovar, went to Raúl’s house to ask him for a replica of the Galibier boots that he had brought back from Europe.

Each pair of Revilla boots carries a part of the philosophy through which Raúl sought to gain a broader view of existence in climbing. Revilla boots and climbing shoes have been handcrafted since day one, and to this day, they preserve the style of that time and the same top-notch quality. Alfredo Revilla, Raúl’s son, keeps this legacy alive from the same workshop where his father worked for decades—and where Alfredo continues to make shoes with the highest-quality local materials and finely detailed manufacturing, honoring the community that has enjoyed them for 60 years. Most ascents of Mexican volcanoes and rock wall climbs were, and still are, done wearing these shoes, undoubtedly marking a “before” and “after” in the sport.

“For me, to receive my father’s legacy in life, both as a shoemaker and a mountaineer, is the highest honor, a great responsibility, and I feel very grateful because this way his name will prevail,” says Alfredo. “He knew that he was unique in what he did, and I have to remain on that line: to be unique and do things well. In this beautiful sport that many of us practice lies our way of continuing to grow, of taking care of our body, our spirit and of healing everything that is within us. It is very important for me to receive these jewels that I will care for with great dignity.”

At the workshop, Alfredo holds a photo of his father, from whom he not only learned a trade but also obtained a legacy. Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mexico. Photo: Alfredo Revilla Collection

But sooner or later, as they say, great passions come back to knock on your door. During the 1980s, Raúl started experiencing painful body aches that doctors could not diagnose. Unable to find relief, Raúl grabbed the only pair of boots he had left. His wife asked him, “Where are you going?” and begged him to keep his promise not to climb. “I have to go,” he replied, “I feel awful.” And he hiked to the summit of El Crestón.

His love for nature and a conviction that the mountains were where he could heal his pain were what made Raúl a great teacher of vertical sports. Perhaps that’s the best way to recognize the heritage he passed down to both his family and community. Along with sharing the secret of how to construct his famous boots with Alfredo, Raúl remained active in the climbing community for more than 25 years after falling ill. He continued to promote mountaineering and climbing, free of charge, through the Asociación Hidalguense de Excursionismo, Alpinismo y Exploraciones and the Instituto Politécnico Nacional, both institutions he collaborated closely with for many years.

“Climbers from around the world came to know Raúl’s reputation. The Maestro is the climber who introduced the sport [to Pachuca] in 1943. It had become an obsession—a quest, like searching for the Holy Grail—for us to meet him,” photographer Bill Hatcher and climber Todd Skinner recounted in a 1991 issue of Rock and Ice. “Everywhere we went, the Maestro was referred to with absolute respect. There is no one in American climbing who everybody admires so strongly. He is their ‘Jorge’ Washington of climbing.”

Raúl will be remembered as a strong and cultured character, a person deeply attached to his principles and an obsessive perfectionist who was committed to his loved ones. He welcomed new generations of climbers into his home until his final days, including Germán Wing, Andrés Delgado and Carlos Carsolio. He always offered them that intimate camaraderie that exists between climbers and conversations full of experience that would later accompany them to the summit.

“He was so important in my life,” Germán says warmly, remembering the house to which so many climbers made a pilgrimage. “He always welcomed me at his home very fondly. I used to travel from Mexico City, step off the bus and walk to Don Raúl’s home. There, at the end of the day, he opened the door, greeted me with a pásale, and then I used to fall asleep in the living room with my sleeping bag. The next day we headed to the Circo del Crestón … I always remember him with much love. I take Don Raúl in my heart for all that he meant and influenced in my life as a climber.”

The legacy Raúl left behind transcends the decades when he completed some of the most revered climbs in Mexico, a time when dozens of clubs throughout the country were created and sought after Raúl to join them. Maestro Revilla led the route to the summits of not only the country’s most magnificent walls but also of teaching, innovation and entrepreneurship in the field of his greatest passion: the mountains. He leaves a bold motto for future generations: “Create solutions, not excuses.”

Raul Revilla Quiroz (1923 – 2022) Father, husband, climber and craftsman. His memory will always be with us. Photo: Emilio Vega Collection.