The Life-Saving Nature of Foam

A look into surfing’s impact vests and the people they’ve brought back home.

On November 13, 2013, Kirk Passmore took off on a set wave at Alligators on O‘ahu’s North Shore, slid down the 40-foot face, fell and never resurfaced. Surfers saw Passmore’s feet pop above the water for a moment, but he seemed to be swimming toward the bottom, presumably from rupturing his eardrum—an injury that can cause vertigo, making it difficult to tell up from down.

Kohl Christensen was sitting on a jet ski when he saw Passmore wipe out and immediately shot toward the impact zone to pull him to safety. He found Passmore’s broken board, with the leash plug ripped out. Despite hours of searching, no one saw Passmore again. Christensen recalled that, on one of the most crowded days he’d ever seen at Alligators, Passmore was the only surfer not wearing any floatation. “I remember Kirk asking me about an inflation vest at some point, but they were expensive,” he says. “I told him he should get an impact vest instead, that they were just as good in a lot of ways.”

An impact vest is essentially a wetsuit top with foam sewn into the upper chest, sides and back that provides static flotation to a surfer without the need to manually deploy CO2 cartridges like in an inflation vest. With an impact vest, if a surfer were to pass out underwater or get knocked unconscious, they would still float to the surface where a rescuer could find them. But on that morning, Passmore was only wearing boardshorts.

“We just kept looking but never found him,” Christensen says. “I think for everyone who knew [he wasn’t wearing a vest], that changed things a bit.”

“If the impact suit has one sole function, it’s to float an unconscious person to be saved,” says Patagonia Product Developer Andrew Reinhart, who calls this “passive floatation.” The suits use the lightest possible foam with the least water uptake and just enough volume to make a surfer positively buoyant while still allowing them to dive under waves.

The foam is concentrated on the sides and back so a surfer can still paddle comfortably; that also means if they are knocked unconscious, when they float to the surface, they’ll likely be facedown. According to Reinhart, however, getting to the surface is the priority. “In my opinion, a facedown surfer who ends up on the surface is a win,” he says, “because then we can get eyes on them.”

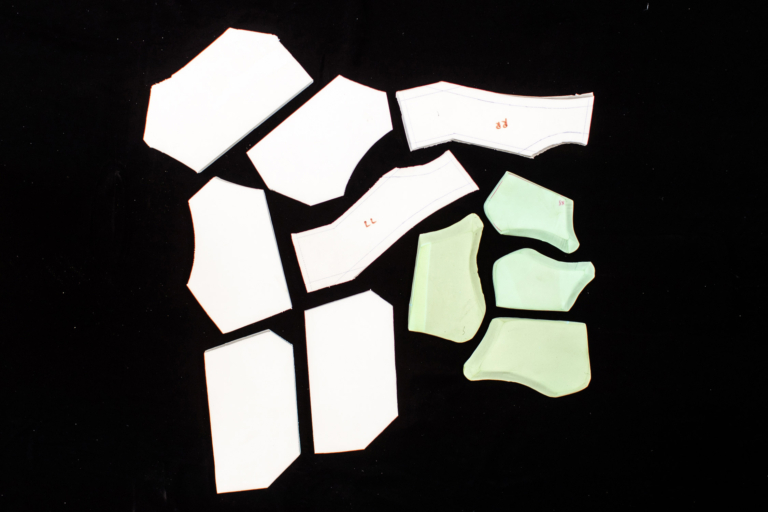

The skeleton of an impact suit on display. Photo: Tim Davis

In 2013, wearing an inflation vest or even foam floatation was still controversial among big-wave surfers. It had been two years since Billabong released Shane Dorian’s V1 Inflation Vest, but a wearable surface aid was still seen by many as a crutch needed only by those who didn’t truly belong in big waves.

“There’s a lot of ego in the sport of big-wave surfing—who’s the toughest, and who can handle a wipeout without floatation,” says Christensen. “It wasn’t an overnight transition.”

That changed with Passmore’s death. “Impact vests weren’t anything anyone looked at twice, and then suddenly we couldn’t keep them in stock,” says Hub Hubbard, product developer at Patagonia. In just one surf season, demand for impact suits nearly tripled and Patagonia’s design team decided to expand the series to include not only the vest but also a short john and short-sleeve spring suit.

When it comes to big-wave safety equipment, the more technologically sophisticated inflation vests are better known than impact vests; they took years of research and development to create, and, in some cases, require a thorough qualification process to purchase. But in their nearly 10-year existence, impact suits have saved more lives than their CO2-powered kin and played a central role in some of the last decade’s most critical surf rescues.

A cohort of Brazilian surfers were the first to regularly wear impact suits in Hawaiʻi. When a few of their team riders began towing Jaws in the late ’90s and early 2000s, the Brazilian surf company Mormaii developed special short john-style wetsuits with built-in foam on the chest and back, and bright yellow handles on the shoulders. “The waves we wanted to surf were more complicated and more serious than the waves we’d been riding before,” says Pato Teixeira, one of those Brazilian surfers. “Even hitting the water at that speed—if we got a concussion, it scared us to have nothing to pop you back up for your friend to pick you up.”

When Teixeira and his friends first brought the suits to the North Shore, other surfers called them “Ninja Turtles” in reference to their shell-like padding. “I knew they laughed at us,” Teixeira says, “but I was using [the suit] because I wanted to get home to my family, so I wasn’t worried about what people said.”

When the leash was introduced to surfing, it was also scoffed at. Now, everyone wears one. Pato Teixeira and Brazilian surf company Mormaii were ahead of their time incorporating foam into their suits. Pe‘ahi, Maui. Photo: Bruno Lemos

Christensen counts himself among the surfers who were dismissive of the suits and now credits the Brazilians for being years ahead in their thinking on wearable safety equipment. “We were surfing outer reefs in boardshorts,” he says. “We thought we didn’t need them [impact vests], but little did we know that we definitely needed them. A lot more people would still be here if we had been wearing them.”

Many other big-wave surfers began reexamining their approach to safety after Sion Milosky passed away at Mavericks in 2011. They began training in CPR and first aid, but such measures would only matter if they could find the surfer in trouble, first.

The impact suit’s ability to provide passive floatation has been the difference between life and death in multiple big-wave rescues in the past decade. In 2012, Greg Long nearly drowned at Cortes Bank when his inflation vest failed to activate before he blacked out. It was his impact vest, which he was wearing over his inflation vest, that brought him to the surface. “He was smart enough to pair his inflation with foam, and that’s why he’s here,” says Reinhart.

In 2019, when Kohl Christensen hit his head at Pipeline, North Shore lifeguard Andrew Logreco rushed toward him on a jet ski. Logreco found Christensen floating facedown and jumped from his jet ski to flip Christensen over, giving Kai “Borg” Garcia time to arrive on another ski to assist. Christensen was wearing his impact spring suit, which had padding on the legs, meaning that when Logreco found him, he was already laying almost parallel to the water’s surface. “If he wasn’t wearing that, I’m 99 percent sure I would have been pulling him up by his leash, and what if his leash broke?” Logreco says. “In those types of conditions, it’s like [looking for] a needle in a haystack.”

Kohl Christensen, Ben Wilkinson and Casey Goepel stand on the shore. Waimea Bay echoes into the valley behind them, their impact suits serve as a reminder of Pacific power. North Shore, O’ahu. Photo: Jean Louis De Heeckeren

Impact suits have also played a lifesaving role by protecting surfers from the dangers posed by their surfboards or shallow reef. Long before Christensen’s accident at Pipeline, the impact suit saved him from a possibly devastating spinal injury. He fell in a barrel at an outer reef, went over the falls and landed on the fins of his board. The impact was so forceful he first thought he’d broken his back. When he got himself to his boat, he saw that the fin had penetrated his impact suit and his inflation vest, barely missing his spine.

Protection from collisions and cuts has led to impact suits being more widely adopted for conditions that might not be 20 feet but still pose a risk. “In the last four years, impact suits have really gained traction in the heavy wave realm,” says Reinhart. “Talk to anyone riding a slab; most likely, they’re wearing foam now.” The lower-back pad on the suits was inspired by an accident surfer Ramón Navarro suffered at a slab in northern Chile, where he landed on his board and broke his tailbone.

Patagonia Australia Hardware Manager Zeb Walsh credits heavy-wave surfers like Russell Bierke and Jamie O’Brien for influencing a new generation of surfers to think more about personal safety equipment. “They see JOB wear it at four to five-foot Pipeline, and it’s brought huge light to the foam suit,” Walsh says. “Now, even at Bells when it’s only 10 feet, younger kids are wearing foam. Kids are much more calculated about safety than we were at their age, and some of their parents are requiring it.”

It’s also becoming clear to the larger surf community that most critical accidents don’t occur in extra-large waves but in smaller conditions when people have their guard down. “By wearing even the smallest amount of foam, the percentage increase of the margin of safety is so high,” says Reinhart. “It’s almost like airbags or a seat belt; by this one little decision, you’re putting your safety into a whole other realm.”

Ramón Navarro pushes through a substantial circle wearing slightly less padding than the “Michelin Man.” Northern Chile. Photo: Jean Louis De Heeckeren

Of course, no piece of safety equipment replaces one’s training, knowledge or preparation. “The foam isn’t going to roll you over and give you compressions, but it’s going to give you that chance,” says Walsh. “Foam needs to be used with a plan.”

Al Cook knows this. In May 2020, off the eastern coast of Australia, he was doing step offs in six to 10-foot waves at a sandbar a mile offshore when his board hit him in the head and knocked him out. His impact vest brought him up momentarily, but due to the turbulence and foam in the water, the vest wasn’t able to keep him floating on the surface. Held under for three waves, unconscious and bleeding, Cook was found thanks to his tombstoning board.

In Cook’s case, it was the group of alert, trained surfers whom he was surfing with that made the difference, but he still recommends an impact suit. “They don’t claim to be a life jacket, and I think people need to understand this,” says Cook. “They provide some buoyancy, but it’s certainly not a guaranteed floating device.”

Even with foam, water rescues can be difficult to execute. Rescuers still struggled to get Christensen out of the water at Pipeline, for example, even with the floatation assistance of an impact spring suit.

Wearable floatation will always only be one piece of a comprehensive approach to surf safety. “You owe it to all the people you are surfing with, and your family, to be prepared,” says Cook. “It’s easy to be the one who gets knocked out, drowns and dies, but it really does affect the people that are left to deal with the situation.”