Special Delivery with Liz Clark

Editor’s note: We’re happy to follow up on Dallas Hyland’s moving tribute to Patagonia ambassdor Liz Clark — after she broke her neck bodysurfing — with good news. Liz’s neck has healed up well and she’s back in Tahiti living on an organic vanilla farm near the boatyard where she’s splitting her time between book writing and boat projects. This story is from Liz’s circle of French Polynesia in early 2012, before her injury, and first appeared on her blog. Glad you’re back Liz!

March 2012: And so the time had arrived. Cyclone season over, it was safe to head southwest say a final goodbye to the Marquesas. I poured over the chart, locating the tiny, isolated atoll of Puka Puka, 250 miles straight south. Raiarii’s grandfather was the first to colonize this desolate atoll in the late 1930s.

Tehani Henere Papa and his wife, Elizabeth, had 22 children there!! Two sets of twins!?! Tehani delivered each one of the babies in a tub behind their little house. They raised the kids on fish and coconuts and the fresh Pacific air. Tehani worked copra from dawn to dusk year round, and when the copra boats came to collect the dried coconut meat that he split, dried, and collected in the large burlap sacs, he could purchase sacs of flour, sugar, and rice with his earnings.

Raiarii’s father, Victor, was number 15 of the 22, and left the atoll at age 17 to find work in Tahiti and had never gone back. Interisland travel is expensive and difficult for locals, with few spots on the cargo ships and high prices for airfare. So Raiarii had never visited Puka Puka, nor met many of the cousins, aunts, and uncles from his father’s side who are still living there. Upon learning this story, I decided we must try to sail to Puka Puka!

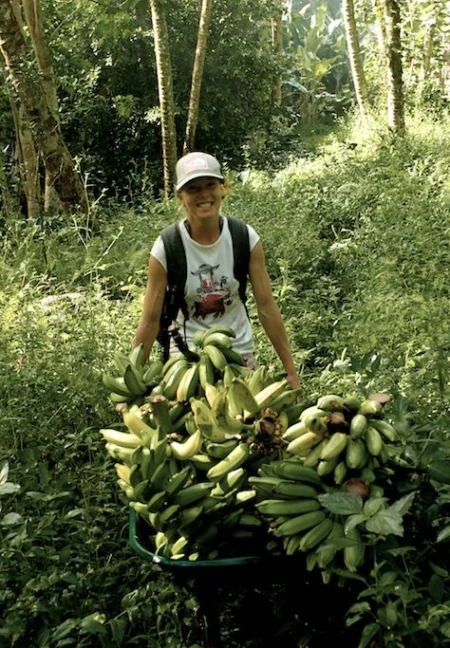

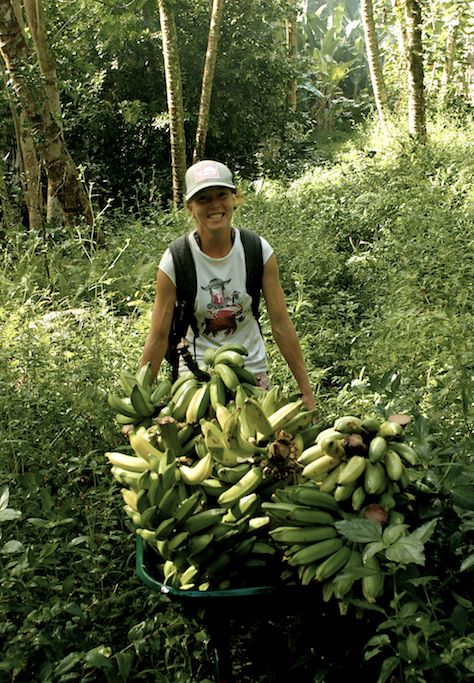

The wind was forecasted to turn north, giving us a good angle to sail there directly sailing, so we prepped Swell and collected fruit from our generous friends to bring to Raiarii’s family in Puka Puka, where the sandy, salty soil lacked the nutrients to plant food. We gathered limes, pamplemousse, oranges, bananas, breadfruit, papayas, starfruit, taro, and pomegranates! By the time we left, Swell’s forepeak was our cargo hold, carrying nearly 400lbs of fruit!

When the wind began to shift northeast, we raised anchor, and slipped around the breathtaking 2,000-foot cliffs, and pointed the bow south. I would miss the plentiful fruit, rugged mountain peaks, wild goats and horses, shaded valleys, cool rivers, and good people of the Marquesas.

Swell’s forepeak converted into the cargo hold for delivering all the fruit.

Goodbye beautiful Enata Fenua!

At sea again, with both the autopilot and the monitor broken, one of us was relegated to the helm at all times. I spent hours watching the sea and imagining our rendezvous at Puka Puka. The atoll has no pass by which to enter a lagoon. The reef extends, unbroken all the way around the island, so I hoped that we could find a safe place to anchor Swell. I’d already decided that either way, I would stand off aboard Swell, while Raiarii went ashore to meet his family and tour the atoll.

On the second day out, the winds lightened and steering grew awfully monotonous, but we plowed through the hot, long day, making mile after slow mile toward our special destination.

Busting some early morning moves at the helm to stay awake, while Raiarii gets some rest.

We hoped to arrive the morning of the third day, but the light winds slowed our progress. His family had been notified of our pending arrival, so we trimmed the sails and eeked every bit of speed possible out of the hull in order to arrive before dark. Finally we spotted Puka Puka’s flat-top of coconut palms on the horizon ahead, and simultaneously, the fishing reel buzzed with a strike. Raiarii pulled in a beautiful tuna. I thanked it for its life with a prayer and quickly put it out of suffering, grateful to be able to arrive with another gift for the family.

Our excitement rose as the island grew clearer. Taking turns at the wheel, we cleaned up Swell and ourselves a bit to be presentable upon arrival. No sooner, Raiarii spotted an aluminum tinny plying the seas in our direction.

Greeted at sea by Uncle Richard, Cousin Teva, and the local policeman.

Raiarii’s uncle, cousin, and the local police officer greeted us on the sea and motioned for us to follow them around to the backside of the island. The men assured us there was a spot up ahead that would be safe for anchoring. A pod of large bottlenose dolphins led the way, crisscrossing at the bow. Soon we were precariously close to the breaking waves on the reef, but still the seafloor did not rise beneath us. “Over here,” they called in Tahitian.

I nosed Swell in carefully, and we watched the colors of reef begin to show under her hull. It was a tiny ledge of reef that stuck out 30 yards more than the rest in about 30 feet of depth, before dropping off into the deep abyss.

Raiarii took the helm, and I jumped overboard to assess the reef for the best spot to place the anchor. With our concerted effort, I directed the anchor underwater to a barren ledge, where it was sure to stay hooked and not hurt much. We also slid a stern anchor over the deep ledge in case the wind switched.

It could hardly be called an anchorage, but the combo of light northeast winds and calm south swell would let us get away with it for this special occasion. Anchors down, we began to offload the cargo. Eyes bulged as the endless train of fruit streamed out of Swell. Filled with fruit, the little tinny rode low in the water. I scurried around Swell, securing a few things and flipping on the anchor light, as they insisted we come to shore immediately to meet the rest of the family and have dinner together. As we pulled away from Swell, I sent up a little prayer for her safety near the reef.

Swell and I were rather nervous about the open ocean anchoring.

Swell and I were rather nervous about the open ocean anchoring.

Off we went in the tinny, the dolphins again at the bow as we buzzed back toward a small crack in the reef with a dock for offloading supplies. We followed a wave into the tiny pass as the whitewater crumbled along the reef on both sides. Uncle Richard neared the dock carefully in the surge, and a splay of arms reached down to help us out. A moment later we stood on land, cloaked in flowered welcome ‘heis’, meeting a lineup of family and friends who’d come to greet us. The kids dove for the bananas and star fruit and we wandered to the house of Uncle Taro, Aunt Patricia, and their four lovely daughters.

Upon arrival.

Raiarii, being shown a photo of his grandfather, Tehani, whose father was Dutch, hence the European features.

Honored by our visit, our gracious hosts fed us until we couldn’t eat anymore as we learned more about the history of the Papa family on the island. Almost a third of the population of 250 were Raiarii’s relations! While eating platefuls of sashimi, poisson cru, and fruit, we listened to stories and looked at old photos of Tehani and the children. It grew late. Weary from our long nights at sea, we asked to be taken back to Swell to rest up for the following day’s island tour and picnic.

Despite my fatigue, I slept little that night. The breaking waves sounded so close I kept sitting straight up and thinking we were on the reef! But by morning I felt assured that Swell was firmly stuck and safe as long as the conditions remained the same.

Raiarii visiting his grandfather’s grave.

Touring town with his cousins.

Precious mini cousin!

Precious mini cousin!

Off to picnic on the east side of the island.

My favorite ride on Puka Puka.

Unlce Taro’s copra shack.

Water nymphs in the serene lagoon.

Puka Puka’s claim to fame: first island in the Pacific that Ferdinand Magellan came upon in 1521.

All the Papa fam aboard Swell.

Boys on the bow.

That morning Uncle Richard came to pick us up and the dolphins again escorted us to the dock. He told us that they loved to swim with people and were always playful and curious when the islanders were spearfishing. I hoped we’d get to swim with them later!

After an extravagant breakfast, we visited Raiarii’s grandparents’ burial site and went to the house where all 22 children were born. Everyone was so delighted by our visit, and the whole day I felt so glad that we’d made the effort to come. After helping prepare for the picnic, we set out across the island in the back of the truckbed, stopping at sites of interest and meeting other relatives along the way. The island had three separate, shallow lagoons on the east side, and we picnicked near the third and swam in the hot, extra-salty water with the kids.

On our return that afternoon, Uncle Taro asked the local mayor if they could launch the community boat so that everyone could come out and take a tour of Swell. He was agreeable, so family and friends piled in and we headed out to Swell. They told us only one other sailboat had ever stopped there as far as they knew, and certainly none of them had ever seen the inside of one. So they were delighted and awed to visit Swell and see that we had beds, sink, oven, stove, water, and all the essentials.

As we all sat aboard Swell, I noticed the waves were picking up. The sets were breaking a little farther out and I’d seen the forecast for south swell on the way. Sadly, I knew we’d have to leave before dark. It was a bittersweet goodbye, having been taken in so graciously and having to part so quickly, but we wouldn’t be safe there again overnight. Many tears were shed as all the family members crowned us with parting shell ‘heis’. Silent drops rolled down Raiarii’s cheeks as he hugged and kissed them goodbye and promised to visit again one day. We waved to their boat until it rounded the corner out of sight.

Just then a big swell lifted the hull and the boat jerked to starboard on the anchor line, reminding us of the reality we faced. The sun was setting, the swell was picking up, and we were getting dangerously close to being tossed onto the reef! We had to get both anchors up before darkness arrived and prepare the cabin for making passage again. As I dove and cleared the anchors, Raiarii pulled them up. I looked around in hopes of saying goodbye to the dolphins, but no sign of them appeared.

Anchors clear, we drifted away from the reef with the wind, readying the mainsail halyard and jib sheets. Just then, one of the dolphins launched into the air beside the cockpit, hovering horizontally for a moment and looking right at us as if to say, “What? Leaving already?!?”

Raiarii and I looked at each other, breathtaken. I jumped in and we took turns swimming with them until it was too dark to see — a magical finish to a magical stopover.

Dusk swim with the welcoming crew at Puka Puka.

We finally dried off and rounded the corner to wave a final goodbye. In the soft dusk, we could see all the family lined up ashore. They flashed their headlights and honked their horns, jumped up and down and waved madly, and we did the same. Slowly we drifted farther and farther away with the wind. We were both sad to have to leave so soon, but grateful that the weather had afforded us those precious 24 hours spent there. After half an hour had passed, we saw the lights of the cars heading home and turned to take on the passage ahead.

As the excitement dwindled, our exhaustion surfaced, and with no self-steering we decided to heave to and sleep for a few hours while Swell drifted away from the atoll on the open sea. I lie there for a while in the cockpit under the stars, spilling over with gratitude and joy. I would never forget our ‘fruitful’ visit to Puka Puka…Time with family is a precious gift! Regardless of our lineage, I hope we will learn to treat each other like the One Great Human Family that we are!! One Love!

Goodbyes are never easy.

Goodbyes are never easy.

We are of the Stars

After leaving Puka Puka, we moved somewhat quickly through the atolls, sailing over a thousand miles in two months with only four stops. Going with the trades was blissful after all the upwind miles we’d previously covered.

We could have waited on the parts to fix the windvane or autopilot somewhere, but rather I proposed it might be interesting to steer full time, having (thankfully) never had to do it. And seeing as there were two of us to share helm duties, it would be much more feasible than when I was single-handing.

I noticed right away that an obligation to steer let me witness more of nature’s magic. It wasn’t as if I never stared at the sea and sky when the self-steering worked, but I could easily be distracted. Now I was glued to the wheel, and an active participant in the scene, as I surfed Swell down the following seas. The waves flowed past the rudder, pulling the wheel right or left. I gazed out at the ocean panorama: ever-changing, ever-wondrous.

Give yourself to the moment, and watch the magic unfold.

Day or night, there were marvels of light to behold. At every incline of the sun, the rays played on the water in their own exceptional way. Sunrise and sunset usually stole the show, but mid-morning’s fresh light uplifted, high noon’s radiance overwhelmed, and mid-afternoon’s bending yellows soothed and foretold day’s end…

Dusk had it’s own charm, too. Shades of gray lined the sky from horizon to horizon, while new stars appeared gradually, as if coming on stage. And when the last remnant of the sun’s glow disappeared, perspective shifted… we were suddenly sailing through the Universe! From horizon to horizon the heavens blazed in all their glory — Perpetual, Supreme, Infinite.

I’d cover the GPS and practice steering by the stars, aligning them with the masthead or halyards. Hercules, Scorpio, or maybe the Pleiades, the chosen star cluster of the hour would hover around the mast as I pulled the wheel back and forth. Cloudy evenings made it more difficult, temporarily hiding the celestial chart. I’d maintain our angle to the wind, checking the compass every now and then. When the winds were light, I might lay back and steer with my feet a while to watch for shooting stars. And If fatigue got too distracting, I’d wake Raiarii and we’d switch for a while.

Despite being rather exhausted, I loved that being present at the wheel for so many hours acquainted me with new-found subtleties of the sea. Plus, I felt closer to Swell than I had in all the voyage. Nothing seemed more effective in learning her quirks, than holding the wheel and letting her tell me herself. Constantly applying my mind to sea, vessel, and sky 12 hours a day, I came to appreciate just how intimately and intuitively the ancient Polynesian navigators would have known their seas.

In the moments where no guidebook or Google or a GPS can tell us what to do, we must blur the lines that separate ‘Me’ from ‘That’. We must feel as much as reason. Listen. Be Present and Ready. Open and Humble. For the Voice within speaks to all of us, though it’s sometimes hard to hear in our distracting modern world. Nevertheless, it’s always there waiting to remind us that We are of the Stars.

We had lucky timing at a few of our stops!

Never know what you might miss when you’re not paying attention!

The Navonics charts had great detail for navigation in the atolls.

Sad to take this beautiful female mahi, but what a blessing her meat was for us and the islanders at the next stop.

Brief renions with friends broke up the passages. Maheata always has a warm meal and smile waiting.