Smith Rock Is Animal Village

Watch the Animal Village place name story, told by Elder Wilson Wewa.

Animation by Jon Yellowhair and oral storytelling by Elder Wilson Wewa of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs.

Listen to the full Animal Village place name story, told by Elder Wilson Wewa.

Transcript

Elder Wilson Wewa: Long time ago before the human people were put on the world. The Creator made everything. The way it was in the beginning of time. He made the earth. And then he made the water. And then. As the land grew when the coyote. And his brother, the wolf created the land. The land grew bigger and bigger. That was the coyote that didn’t want to be lonely on this world. And so other animals were created. Bobcat and elk. Deer. Cougar. Fish were put into all the waters. And in that time. All the living creation, all the animals. They could talk to one another. They had a common language. And so they. Subsisted side by side on the land. For many, many years. And they had villages across the land where they stayed. And took care of one another. And where they gathered the foods from the land. That helped to keep them alive. But as a part of the creation. There were beings, giants that were created also. And they roamed the land. As far as you could see. And they didn’t want to live side by side with the with the animal people. And because they didn’t want to live side by side. There came a time when they started to. It. The animal people wherever they found them. And when they would cross the land, their steps. Woo! Woo! Woo! Step in. The whole land would shake. And all the people would would run into hiding wherever they were at dug holes and put mats over himself or they went into caves or when did the thickets. And he had. And that giant was called New Whistle. And he would carry a long stick like a walking stick with a point on one end. And that’s what he would stab the people with. And he would carry a big. Stone Bowl on his back. And that bowl was for grinding the people. And so when he would go, you could hear him coming like thunder. And everybody would. Run into hiding. Well, that went on for for ages. And the time came that the people were getting less and less. And so the animals approached the leader of all the people, which was Aesha, the wolf. And said something has to be done. To get rid of the new weasel, because if we don’t get rid of him, pretty soon, there’s going to be no people left. So they met all the animals. All the villagers came together and met. And then somebody says would. The only one that would be smart enough. Crafty enough to. To destroy a whistle. It’s up to. Coyote. That caused the uproar. Everybody know we don’t want him. He’ll ask for pay. He’ll ask for this. He’ll. He’s unreasonable. When he does something, you know, he’ll never let you forget it. We don’t want him. We got to find another way. And after that, it broke up. The meeting broke up and everybody went their way and everybody had that thought in their mind. Of how they would get rid of it. And then he came. He was a hawk, came across the land and everybody heard that. Thundering sound and it could hear his footsteps. And they ran into hiding and he stabbed some more people and put them in his bowl and. He would go and he’d look to all different directions. He had to look look all around to see if he could see smoke going up from. The fires. Or if the breeze would blow. If he could smell, he sniffed around in the air and he’d look around to see if he could smell the people. The scent of the people. And then he kept on going. As he killed more people to eat, they came back together again to meet with each. And they they relented, then go ahead and ask coyote. Coyote to get rid of. And there was a whole. So. Aesha went to go look for his little brother eats. And when he found him. He told him that the. People had agreed to let him. Get rid of the new whistle. And so. He said, wanted to write off of the conversation. He said, Well, what are you going to do? What are you going to pay me? And so he thought about it. He said, Well, all the people will be able to pitch in food for you and you’ll be able to make it through the winter. But he didn’t want just food. He wanted more than that. He wanted Wolf’s daughter because she was real pretty. And the wolf didn’t want the eats for his son in law because he’s. Too much of a braggart and a liar and and everything else. And he really didn’t want him for son in law. But finally he also relented to allow coyote. If you get rid of him. You can marry my daughter. So. It became real happy. He was just really elated to. Knowing that he would marry each US daughter. But at the same time, Isha, the wolf was thinking in his mind, as crafty as it is, he’s probably going to get eaten so there won’t be a marriage. So Coyote was preparing himself to battle against the new whistle. And so he told the people on this day, on the day that he made he said, everybody will go into hiding and nobody will come out until until I direct you to. So as that day drew near. He went and gathered sagebrush to make a fire. Dried sagebrush. Out in the open. He piled all the sagebrush up in the open. And then he pulled out from the ground. Green sagebrush. And he made a flier. By that time, everybody knew that was the day. They all went back into the thickets and caves and they dug holes and pulled brushes on top of themselves or covered the tops of the hole with mats. And they hid. And also a came across the land. Woof, woof. They could hear him come in like thunder. And he was coming. And he would look all around to the south and to the east and to the north and to the west. And he couldn’t see anything. He couldn’t see any sign of life, any place. But he knew that he had not eaten up all the people. So he kept going. In the meantime, it’s lit the fire. And he got it going really hot because sagebrush burns really hot. He got it going really hot and after was going pretty good, he throwed the green sagebrush on there and the green sagebrush sent up big clouds, big plumes of smoke. And he starts singing and talking to himself really loud to draw. There was also attention. So as news of what was going along, looking all around every direction, he could smell the smoke. Oh, I could smell smoke. Somebody has a campfire, so he start looking really well wherever he could see. And then he seen that plume of smoke going up. There’s a village right there. So he had it that way. The ground was shaking then. Thunder. Thunder. He saw and see where. All the animals were scared in the caves and underground and in the thickets because they didn’t want to get found. And they thought he might smell them. And they were just really afraid. And when news came out on the that flat coyote was sitting there poking at this fire. And he walked upon the. Aren’t you afraid of me? Coyote turn around. Looked up at him. Way up in the sky. Who are you? Don’t you know who I am? I’m going to eat you for supper. Oh, there’s nothing here to eat. I’ve looked. I’ve looked everywhere. There’s no nothing to eat. No mice, no squirrels, no anything. Nothing to eat. I’m going to eat you. Oh, you can’t eat me. I’m too skinny. I’m starving. I’m going to eat you anyway. Coyotes as well. I’ll tell you what. We’re going to have a contest. To see who is the strongest. Whoever wins that with the winner will get to determine who is going now, who is going to take control. So coyote towing, well, race will run across the land for us. We can go that mountain over there, will run around there and come back. Will come right back to my fire. And there was a look down there and know. I don’t know. I don’t trust Coyote. If we race, he’s going to beat me. No. I don’t want a race. I don’t want to race you. Coyote thought about, well, what do you want to do? And so I was always thinking there. Then Coyote says. Take your ball off and put it on the ground. So he put it on the ground because it was real heavy. So he put it on the ground. So you walked around there. Walked around in the candy. That’s a nice, nice bowl you have. So he crawled up on the edge and he was looking in and he said, then it’s all dark in there and red as red spots in there. And then there was Gleam and then you’re going to join those red spots. He says, I know what we’ll do. We’ll have a contest of strength. One of us will crawl in the bowl and the other one will use your pounder. The pistol and you’ll raise it up as high as you can. Raise it and throw it down. And now whoever wins, whoever smashes the other one up will win. Be the winner. There was a thought about it now. Well, he’s kind of scrawny looking, and I think he’s going to lose. All right. We’ll do that then. So. Coyote. Well, you get in there first. Oh, no, I’m not going to get in there first. So they. I had a little contest to see who was going to get in there. And Coyote lost. So he was the first one. So he crawled up on the edge like he was going to crawl in there. And then he said, Oh, look over there, way over by that mountain. There’s smoke going up, there’s some other people. And then there was a hot turn around to look at. Coyote took off his fear and throw it in the bowl. Then he jumped down. He had a hole dug. He grabbed the sagebrush next to it and pulled it on top of him. And then there was a hot turn. That’s not smoke. That’s a cloud. Oh, I must have been deceived. They made his voice go inside by his fur. Then he looked in there. Your first, you get three chances. You can raise that rock as high as you can and you get three chances. And if you don’t break me to pieces, then I’ll be my turn. So Nosal lifted up the rock as high as he could, and then he wrote it down with all his might than even the hit he could hear just crack when it hit the bottom of the grind and around coyotes. Oh, gee, that feels real good on my back. Bush harder nosed, got mad and he lifted it up and he hit again. Oh, that feels again. And he lifted. Oh, he was mad. And he’d throw it in there and grind it around coyotes. It all felt good. My back feels real good. This is why it. Then there was a house and I got two more times. Well, do it fast. He quickly. So he lifted up and then he hit it. Oh, that was right on my neck. My neck was or he said that felt good and it was all got bad and lifted up again and hit. You’re using up your all your your chances. You only have one more time. So he lifted it up and he jumped up in the air high as he could jump. And then he came down, hit in the ball and heard that ball just crack really loud. He grinded it around and cried. He said, Oh, that feels good. Grind it some more. That’s where that itchy spot was on my back. That feels good and all. And it was all just round and round and round and round. He was so mad. He was infuriated. The coyote said, okay, I didn’t die, so it’s my turn. So he said, I think you’re wrong, though, because I can smell smoke. I think that is smoke. So it was hot, turned around to look again and Coyote got out of the home and jumped in there. Put on his fur. Come crawling out of that. Crawling out of that bull. Up on the edge. All his for all bloody and everything. All tattered and all puffed up and everything. Standing on the edge, there was a turn around and looked at him and he said, You have to get in there. Now it’s your turn. He looked and you know, how did he survive? He’s still alive yet. But in those days, every creature on earth was honorable. And so he crawled in the bowl, hunkered down, and Coyote picked up that pistol and threw it down with all his might. He called on his powers. He had some magical powers that made him who he was. And he called upon them. And when he throwed the rock down. It cracked the back of an ozone hole. He almost died and he lifted it up before he could crawl out and come back for vengeance. And he threw it down again and hit him on the head and put a big bump on his head. And he was getting ready to put his hands up on the edge to crawl out, and Coyote jumped as high as he could and brought that rock down and hit him one last time. A fatal blow. And while he was agonizing and kicking around in that bowl, he kicked out the south side of the bowl and rolled on to the ground. He was rolled in this way and cry in agony and rolling all over the ground. And Coyote watched him crawl upon the edge of the rim of the bowl and watched him. And finally he died. Coyote got rid of him. And today. That place we call Fort Rock. That’s the top of a bowl, because through the ages, it got buried under the ground. And just the top is sticking out in the south. Part of the bowl is busted out. And to the south of Fort Rock, the hills there is called Connolly Hills. That’s the news where he died laying there. And to the east and to the south and even to the west and to the north. All around Fort Rock, you see. Those little bitty, tiny heels all pushed up. That was where he rolled this way and that way and kicked and made the ground pile up. And while he was bleeding. You look over that land or you walk across that land, there’s spots there where there’s red dirt. That was his blood that he. That dripped all over the place. And his stick that he had when he was on his last part of his dying. He was trying to stab Coyote with Coyote. He was running this way and that trying to stay out of his way. And when he stabbed his last. Stab the ground. He fell. That’s when he fell down and his stick cut into the ground. And to the east, there’s a place called crack in the ground. And his stick rotted away in the ages and his body still laying there today. He carried a smaller basket. And that basket is to the southeast. Of Fort Rock. And. He had all the root foods in there and all his dried meat. Bighorn sheep, dried meat and deer meat and low and bare and everything he had there. And there’s all kind of root foods in that basket. And that sat there through the ages. And when the world was changed for the coming of the humans, it got turned into that beauty. And when we would go by there, my grandma used to say, Tell me, I always want to go up on that. Butte. Because in the legend time they said that was the basket of the new hall. Had all the food in there. And she never did go. She passed away when she was 107, but she never did go. But I went. They made a road on there to put. Radio towers up there. And so we went on a tour and they took us up there and it was in the late spring. And I see in five different species of roots up there that we use for food. And when I walked around the edge of the Rimrock, there was the stone walls for hunting deer and. And bighorn sheep. And you could see out in the desert the other walls that were used for hunting and look. I thought to myself about the legend. I said, My grandma never, ever came up here, but the legend that she knew was true. All our foods grow on this. Little beauty. Just the way in the legend. And from up there you could see that Connolly Hill’s going out for way I don’t know how many miles it is, maybe four, four miles long. Of his body still laying there with the red around it where he bled to death. And when he cried, when he was in agonized, agonizing cry and. His cry, his tears made all those lakes around there, and there’s no no fish in there. All those lakes are too salty for fish. That’s news. Those tears, Silver Lake, Summer Lake, Albert Lake. And our people had stories all over the land. Because there wasn’t only one. There was there was several. And through time, Coyote destroyed them all. There was the Animal Village at home. Today they call it Smith Rock. All the animals lived there. Badger squirrels, mice, the bighorn, sheep, people. All the animals lived there. Bear elk. They all lived there at the Animal Village. And one day there was a found them, and they all ran into hiding. And as he was searching those hills for them and going around and Coyote was coming down the river from the east. And as he was coming in, he could see who was looking over to the ridge. And he said, that’s the last one. From this time on, he said, I’m going to use this magic powers. From this time on, I’m going to turn you into stone. You’re never going to eat people again. You’ll remain right there forever. And he turned into stone. And he’s still standing there yet. The West Side of Smith Rock. And now just that one stone is still there. No wizard standing looking over the ridge forever till the time the world will turn itself around. And one day it’ll become alive again. And that time at the end of the world.

Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs Elder Wilson Wewa. Though the stories of his ancestors are traditionally shared orally, he has gathered many of them in his book, Legends of the Northern Paiute, which includes a telling of Animal Village, so that they may be shared with those unable to hear them from an Elder. Photo: Tara Kerzhner

Editor’s Note: As an Indigenous climber born and raised in Bend, Oregon, Tara Kerzhner has had a lifelong relationship to Animal Village, also known as Smith Rock State Park. While Smith Rock is considered the birthplace of American sport climbing, it is also a place that Tara has been visiting since she was a kid. After discovering NativesOutdoors through the climbing community, it wasn’t long before she began learning about Place Name Stories from Len Necefer, who recounted the creation story for Shiprock, New Mexico, on the Navajo Nation. These stories sparked a fire within Tara to continue learning Indigenous creation stories for the places and landscapes that she connected with the most.

Like many generations of people before her, Tara sought out Elder Wilson Wewa of the Confederates Tribes of Warm Springs to hear the creation story of Smith Rock. By honoring the oral storytelling tradition of Indigenous people and sharing the story more broadly, Tara hoped to grow knowledge and respect within the non-Native climbing community about the lands we recreate on. Here, Tara and Len Necefer, founder of NativesOutdoors, talk through what it means to be part of a younger Indigenous generation finding connection to the land through sport, and what non-Indigenous climbers have to gain from Indigenous storytelling and traditional knowledge. Their conversation below has been edited and condensed for clarity.

A Conversation between Tara Kerzhner and Len Necefer

Transcript

Len Necefer: We met a few years ago, and one of the places that we talked about early on was Smith Rock. I didn’t get there until years later, but this is a place that you have a lot of relationship to. I’m curious if you could articulate that relationship to Smith Rock as an Indigenous person, as a climber and through your own family’s relationship to this place.

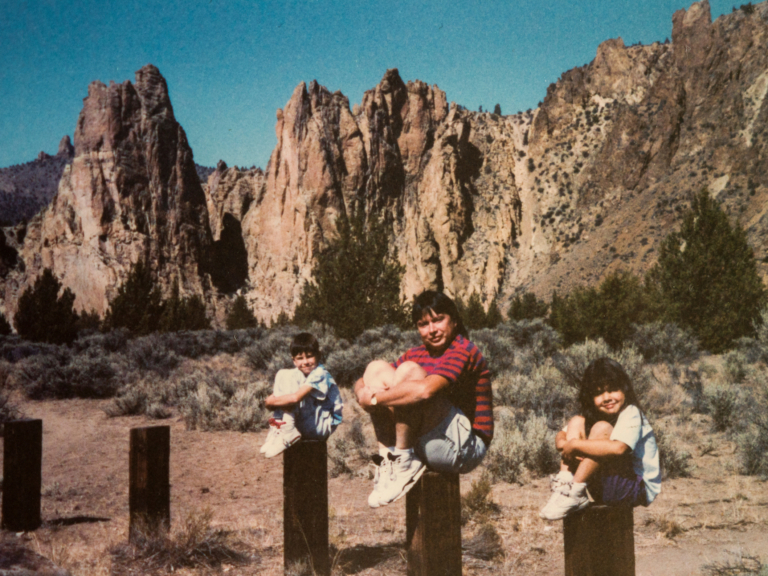

Tara Kerzhner: I’ve been going to Smith Rock since I was a little girl. We’d always do the Misery Ridge Trail hike up to the Monkey Face. I have a lot of childhood memories of going there. My dad had always been like, “I’ve climbed all these rocks.” He would always say that. Even though he never traditionally climbed, like never put on a harness or did any of that, but he did scramble around Smith Rock quite a bit growing up. So, he already kind of had a relationship as a climber in his mind to that place.

I didn’t really start climbing until much later. But growing up in Bend, Oregon, which is just a stone’s throw from Smith Rock, that was the first place I climbed outside. It became a place that I started going to many, many times a week. I was living in my car and just trying to be there as much as possible. And then I fell in love with it in a new way, which was to photograph it, and it became my favorite place to photograph as well. I feel like it’s this long relationship that’s evolved over time. And now it feels to me like one of the more special places in the world. When my dad died, that’s the first place I went. I just drove to Smith Rock and watched the sunset.

Len: The reputation of Smith Rock is this hard place that’s kind of chossy, kind of sharp. When I think of climbing, that’s one of the pinnacles this place is lauded for—being a test piece, historically. But you mentioned your dad, so it’s this place of refuge as well [for you]. It’s integrated in your life in a larger way beyond climbing. Could you talk about that or what that looks like for you?

Tara: Smith Rock is the birthplace of American sport climbing. Some of the very first hard test pieces were put up there. To Bolt or Not to Be was the first 5.14 in America. I don’t really remember seeing the climbers when I was growing up, but when I did start climbing, I looked up at these routes and they always seemed very intimidating. Smith Rock is made of sharp, petrified hummus. It’s a difficult place to climb, but I cut my teeth there as a climber. I’ve really climbed a lot there and had some of my prouder climbing achievements there. So, it’s an interesting, very historic place in climbing. And it’s interesting to me to have that history of my family’s relationship to that place and then tie that into the history of climbing.

Len: Could you tell me more about your family’s relationship to this place?

Tara: My great-grandmother Isabel Saunders was a well-known Elder of the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho; however, many of the Pacific Northwest tribes are connected, and she was known within the Warm Springs community as well. Because he was adopted, my dad was never able to complete his family tree, and we were never enrolled as members. We are also Umatilla, Nisqually and Saskatchewan. Some of our blood family does live in Warm Springs, and I remember as a kid going to powwows in Warm Springs, which is very close to Smith Rock.

And this whole time, I didn’t really realize what Smith Rock’s significance to the tribe was. I kind of didn’t really think about it. I just knew that I really loved that place, and we’d been going there for a long time. It wasn’t until much later that, through you, I discovered these creation stories to recreation places.

Len: We did that trip out to Shiprock, [New Mexico,] in the Navajo Nation where I’m from during the COVID-19 pandemic. I remember we talked about the history of climbing, and we saw those bolts on Shiprock that are illegal. Just navigating that relationship between climbers and tribes is kind of a fraught one. And one of the ideas that we both had [for this project] was having someone from the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs or a Native person in front of the lens. And we kind of had that moment where we thought “Oh, maybe it’s you.”

Tara: Well, I’m a photographer first. I love photography, and I am a climber to my core, but I prefer to be behind the lens, not in front of it. I just really enjoy expressing myself through photography versus being the climber model. And I had this idea for this story that it would be very cool to photograph maybe a runner even or a hiker. But it would be very cool to find a climber. And so I started digging and trying to find a climber from the Warm Springs tribe. And the reaction I got was probably the reaction I would get in a lot of places, which is just that nobody climbs here. I don’t know if that’s entirely true. I’m sure that there are some people I didn’t reach, but [many said] that it’s a white person’s sport. And that, you know, we don’t really do that. I think that was the quote: “We don’t do that.”

So I realized that the only way to make this story happen was to forfeit my camera and tie in.

Len: To your point, when we visited Shiprock, it almost felt like a mirrored story of the relationship of Native people and climbing. Those phrases of, “Oh, we don’t do that. We don’t climb,” is something that I heard within my own community as well. A lot of those folks who say that are Elders. Could you tell me who Wilson Wewa is and how you met?

Tara: It was very cool to meet Wilson. I generally feel pretty intimidated talking to Elders. Because I didn’t grow up on the res, I always sort of feel like I’m out of place. I was nervous, but I was so happy he agreed when I asked if I could interview him and record the verbal telling of Smith Rock’s creation story. He’s already recorded this in a book as an author, but in talking to you, I understood that these creation stories were originally, and are still, passed on verbally. And so I thought it would be cool to get a verbal telling of the story, because it felt more authentic and respectful. Like, the best way to share the story is the way that it should be shared.

Interviewing him definitely felt intimidating at first, but he was super nice. After we finished, we went outside, and I took his portrait. My dad was a lapidary artist, and I gave him a rock that my dad made. I photographed him holding it, and he asked me what my family names were. I told him the name of my grandmother, my dad’s mom and the name of my great-grandmother. And both women he knew personally. It was the first time in my life that I’d ever met anyone outside my parents who knew my great-grandmother. It immediately made me feel comfortable, like I wasn’t out of place. Like I belonged there.

Later, he texted me photos of some moccasins that my great-grandmother had beaded. She was a really well-known bead artist. To see photos of her work meant a lot to me.

Len: It’s kind of crazy that your connection to Smith Rock more deeply connected you to your own community in this roundabout way.

Tara: Yeah. My dad was adopted, so we were completely removed from our Native family and relatives. I still don’t really know who they all are. So it was really cool to make that connection with Wilson.

Len: So much of our identity is traced back to this thing called blood quantum, which is not a Native concept. Whenever you go into Native communities, they ask you who your family is, first. And of course, Wilson asked you that and knew your family. There is a connection here.

It’s kind of funny that in terms of carrying on a connection to landscape, you’ve done it in your own way through climbing. And I know that was a point of tension in that conversation with Wilson, the role of climbing on this landscape. For you as a Native person, it’s connected you to this place, but for Wilson, it’s something that he views more negatively. Could you talk about his view on climbing?

Tara: I recorded the verbal telling of Animal Village and then we chatted a little bit about climbing because he knew that I was going to be photographing climbing. When I asked him how he feels about the climbing at Smith Rock, he said very strongly that he does not like it, that it hurts the landscape. It’s eroding the earth. He doesn’t like the bolts. He doesn’t like the chalk. And he doesn’t like what it’s doing to the place. And as someone who clips those bolts, puts that chalk on the wall, stomps around on the base of the climbs and contributes to erosion, I felt bad immediately.

I think that the first time I ever heard that Native people didn’t like climbing was when we were talking about Shiprock, so it wasn’t like it caught me totally off guard at all. It was just a strong opinion from someone I respected a lot. I guess I knew that all along leading into this—because one of the reasons I wanted to do this in the first place was because I felt like if non-Native people knew the creation stories, they would fall in love with these places as much as Native folks, or maybe they’d fall in love with Smith Rock as much as I have fallen in love with it. And they would treat it better and be better stewards to the land. So it was coming from a good place of doing this project. But I think as someone who is part of that impact, when he said that, I kind of just took it in.

Len: I think that’s been one of my learnings as I’ve gotten older. You hear what the Elders say, and it always becomes this question of like, well, what’s better? Is it better if a Native person isn’t connected to a landscape? Do impacts that happen from climbing outweigh the benefits of reconnecting Native people to the landscapes that we’ve been attached to for thousands of years?

In terms of that Elder-to-young-person dynamic, it’s a conversation. Where I’ve come to with climbing and skiing, if I get some pushback from Elders, I’m like, well, had I not done these things, I wouldn’t have learned these ceremonial songs that are attached to these landscapes. I wouldn’t have learned some of these creation stories. And I wouldn’t have been an advocate for protecting these places in the way that I am now. And is that a worse position than we were in before had that not happened? I would say climbing allowed you to reconnect with the landscape and have this conversation with Wilson. And I don’t think he’s ever probably met a Native climber before.

Tara: I definitely think that was a first. And if it weren’t for climbing and photography, Smith Rock would have been a place that I would’ve thought about but wouldn’t have connected to like I did. It would never have led me to learning about the creation story and asking myself the questions of like, is it OK that I have this impact?

Len: Yeah. And in terms of carrying on legacies, you know, Wilson and our Elders aren’t gonna be around forever. It’s our responsibility in many ways to learn the things that they have to teach us, but at some point, we’re gonna occupy that role.

Tara: I think that when more Native people start climbing, this will be a lot different than it is now. In bringing more Native people into these sports, skiing or climbing or whatever it is, you’re inviting different perspectives and a more empathetic view of the land than you might have from someone who literally never had any knowledge given to them about the importance of the land outside of simple stewardship.

It definitely makes me feel like I have a responsibility now, because I know a little bit more than some of my peers in the climbing community. But that’s why I wanna share those stories. Because I think that if people can see this and know how deep the Animal Village place goes and the importance for Native people, I think that that could really change the way that people choose to interact with that place. And maybe through our efforts, can chip off a little.

Len: Yeah, I mean, history and society have so much momentum behind it. The best that we can do is change the course by a degree. But in the same token, climbing’s what brought you closer to understanding your own relationships with land.

This is a very Navajo perspective, and it’s not reflective of all tribes, but I was always taught that everything has good and bad within it. Everything’s a mixture of those two. And whatever comes out or whatever’s prioritized is what will be shown. And I think especially around climbing, my own community has a very tumultuous history of climbing on our sacred rocks. There’s a climbing ban across the res.

But what I’m seeing with a lot of younger folks that are starting to climb is that they’re starting to become curious of the landscapes that they’re spending time on, because we’re not sheepherding and doing all these things that traditionally connected us the land. And I say, well, you know, this has an impact, but I think the impact from Native kids not being connected or Native peoples not being connected to the landscape is a way greater harm than the impacts there. In terms of our lived experiences, there’s some understanding that we wouldn’t be having this conversation had it not been for climbing.

Tara: Totally. I do think that it’s worth questioning yourself as a climber or a skier. It’s an important question to ask yourself, is this OK? And I think that could be that degree change for you, or hopefully more than a degree, at the very least in how you respect the places that you’re recreating on.

Len: Right. I would say the Navajo worldview is not feeling entitled to a landscape.

In sharing this story, you alluded to this a little bit before, but what do you hope for non-Native climbers who climb at Smith? What should they take away from this?

Tara: I think originally it was, look at how beautiful this incredibly in-depth creation story is. Listen to it. Take it in, understand how sacred and meaningful this place is and has always been to Native people, to the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs and other Northern Paiute.

Understanding is part of learning to respect it. Knowledge brings empathy. The more knowledgeable you are, the more understanding you have, the more empathetic you can be to something you may not have understood. If you know how important this place is to Native people, and how incredibly beautiful the story is, it completely changes the way you look at the landscape.

I mean, you listen to what Wilson is saying. In my head, I was living this story in my mind and animating it inside my brain. And knowing Smith Rock so well, and Fort Rock, I could really envision exactly what he was saying. And then I retold it to a bunch of people. Cause I thought it was so cool to connect deeper to this place. I guess my hope is that people will find it as cool as I do—because I think if they do, then it will change the way that they feel about the place.

Len: Yeah. I’m from the desert Southwest. We have big rocks out there, but to hear another story from another place, it felt like an animation. Like I was living in that story. And having spent a little time at Smith Rock, it gave me a deeper respect and understanding for that place. Because quite honestly, you go to that park and there’s not really a whole lot of acknowledgement of Indigenous people. And I feel like that’s a loss for the people that visit because that’s a whole layer of history. Thousands of years of history in addition to the climbing and stuff that’s already there.

Tara: They have these little plaques up there. It’d be sweet if they had one that just said the original name for Smith Rock. I mean, Smith Rock is kind of a lame name in general. And [the name] Animal Village, if you’ve spent any time in Smith Rock, makes a lot of sense. You’re just walking down the river and there’s otters and bald eagles, baby bald eagles.

What I like about the Animal Village is that you immediately recognize how that place is used by the animals [who live there], they’re living off the land. And so instead of a place named after a dude named Smith, you’re immediately recognizing that the land is more valuable than someone’s name. The land is valuable because the animals live there, and they need the land to survive.

Len: It was named after John Smith, who was the Linn County sheriff and Oregon legislator in the 1850s and 1860s. A newspaper article credits Smith with “discovering the rock.”

Tara: Oh, wow.

Len: Another story claims the rock was named after a soldier named Smith who fell to his death from the rock in 1863 while the unit was camped nearby. Whatever it was, I think the name Smith Rock really diminishes the vibrancy of that place.

Tara: It does. I totally agree. I think a lot of places are being renamed these days. I would love to see Smith Rock renamed officially to Animal Village. That’d be so sweet.

Len: Animal Village State Park would be awesome.

Zooming out, we’ve talked about Shiprock and how it led to this conversation about Smith Rock, but there’s a lot of places that have creation stories where we climb and do these sorts of things. Could you talk about the importance of that and what we should be thinking about moving forward?

Tara: Yeah. I think it’s, take this as a lesson for every place that you like to recreate in. And if you’re a nerd like me, you’re gonna start looking up the creation stories for all the places you like going to. There are so many places that we recreate in that have these Indigenous place names stories.

Len: Yeah. Once you get that taste, it becomes really interesting. It’s this whole layer of history that adds a whole new level of depth and curiosity.

Tara: Imagine if history classes just taught Place Name Stories!

Len: “Now we’re gonna have you jug up El Cap and recreate the story of the inchworm.”

Tara: Oh yeah. Jugging up El Cap truly is the inchworm.

Tara treads old ground on the Misery Ridge trail, a hike she’s been doing since she was a girl. Animal Village. Photo: Jules Jimreivat

Len Necefer: We met a few years ago, and one of the places that we talked about early on was Smith Rock. I didn’t get there until years later, but this is a place that you have a lot of relationship to. I’m curious if you could articulate that relationship to Smith Rock as an Indigenous person, as a climber and through your own family’s relationship to this place.

Tara Kerzhner: I’ve been going to Smith Rock since I was a little girl. We’d always do the Misery Ridge Trail hike up to the Monkey Face. I have a lot of childhood memories of going there. My dad had always been like, “I’ve climbed all these rocks.” He would always say that. Even though he never traditionally climbed, like never put on a harness or did any of that, but he did scramble around Smith Rock quite a bit growing up. So, he already kind of had a relationship as a climber in his mind to that place.

I didn’t really start climbing until much later. But growing up in Bend, Oregon, which is just a stone’s throw from Smith Rock, that was the first place I climbed outside. It became a place that I started going to many, many times a week. I was living in my car and just trying to be there as much as possible. And then I fell in love with it in a new way, which was to photograph it, and it became my favorite place to photograph as well. I feel like it’s this long relationship that’s evolved over time. And now it feels to me like one of the more special places in the world. When my dad died, that’s the first place I went. I just drove to Smith Rock and watched the sunset.

Len: The reputation of Smith Rock is this hard place that’s kind of chossy, kind of sharp. When I think of climbing, that’s one of the pinnacles this place is lauded for—being a test piece, historically. But you mentioned your dad, so it’s this place of refuge as well [for you]. It’s integrated in your life in a larger way beyond climbing. Could you talk about that or what that looks like for you?

Tara: Smith Rock is the birthplace of American sport climbing. Some of the very first hard test pieces were put up there. To Bolt or Not to Be was the first 5.14 in America. I don’t really remember seeing the climbers when I was growing up, but when I did start climbing, I looked up at these routes and they always seemed very intimidating. Smith Rock is made of sharp, petrified hummus. It’s a difficult place to climb, but I cut my teeth there as a climber. I’ve really climbed a lot there and had some of my prouder climbing achievements there. So, it’s an interesting, very historic place in climbing. And it’s interesting to me to have that history of my family’s relationship to that place and then tie that into the history of climbing.

Animal Village, and the Kerzhner siblings, in the ’90s. Photo courtesy of Tara Kerzhner

Len: Could you tell me more about your family’s relationship to this place?

Tara: My great-grandmother Isabel Saunders was a well-known Elder of the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho; however, many of the Pacific Northwest tribes are connected, and she was known within the Warm Springs community as well. Because he was adopted, my dad was never able to complete his family tree, and we were never enrolled as members. We are also Umatilla, Nisqually and Saskatchewan. Some of our blood family does live in Warm Springs, and I remember as a kid going to powwows in Warm Springs, which is very close to Smith Rock.

And this whole time, I didn’t really realize what Smith Rock’s significance to the tribe was. I kind of didn’t really think about it. I just knew that I really loved that place, and we’d been going there for a long time. It wasn’t until much later that, through you, I discovered these creation stories to recreation places.

Len: We did that trip out to Shiprock, [New Mexico,] in the Navajo Nation where I’m from during the COVID-19 pandemic. I remember we talked about the history of climbing, and we saw those bolts on Shiprock that are illegal. Just navigating that relationship between climbers and tribes is kind of a fraught one. And one of the ideas that we both had [for this project] was having someone from the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs or a Native person in front of the lens. And we kind of had that moment where we thought “Oh, maybe it’s you.”

Tara: Well, I’m a photographer first. I love photography, and I am a climber to my core, but I prefer to be behind the lens, not in front of it. I just really enjoy expressing myself through photography versus being the climber model. And I had this idea for this story that it would be very cool to photograph maybe a runner even or a hiker. But it would be very cool to find a climber. And so I started digging and trying to find a climber from the Warm Springs tribe. And the reaction I got was probably the reaction I would get in a lot of places, which is just that nobody climbs here. I don’t know if that’s entirely true. I’m sure that there are some people I didn’t reach, but [many said] that it’s a white person’s sport. And that, you know, we don’t really do that. I think that was the quote: “We don’t do that.”

So I realized that the only way to make this story happen was to forfeit my camera and tie in.

Tara finds a sliver of shade on The Northwest Corner (5.12a). Monkey Face, Animal Village. Photo: Jules Jimreivat

Len: To your point, when we visited Shiprock, it almost felt like a mirrored story of the relationship of Native people and climbing. Those phrases of, “Oh, we don’t do that. We don’t climb,” is something that I heard within my own community as well. A lot of those folks who say that are Elders. Could you tell me who Wilson Wewa is and how you met?

Tara: It was very cool to meet Wilson. I generally feel pretty intimidated talking to Elders. Because I didn’t grow up on the res, I always sort of feel like I’m out of place. I was nervous, but I was so happy he agreed when I asked if I could interview him and record the verbal telling of Smith Rock’s creation story. He’s already recorded this in a book as an author, but in talking to you, I understood that these creation stories were originally, and are still, passed on verbally. And so I thought it would be cool to get a verbal telling of the story, because it felt more authentic and respectful. Like, the best way to share the story is the way that it should be shared.

Interviewing him definitely felt intimidating at first, but he was super nice. After we finished, we went outside, and I took his portrait. My dad was a lapidary artist, and I gave him a rock that my dad made. I photographed him holding it, and he asked me what my family names were. I told him the name of my grandmother, my dad’s mom and the name of my great-grandmother. And both women he knew personally. It was the first time in my life that I’d ever met anyone outside my parents who knew my great-grandmother. It immediately made me feel comfortable, like I wasn’t out of place. Like I belonged there.

Later, he texted me photos of some moccasins that my great-grandmother had beaded. She was a really well-known bead artist. To see photos of her work meant a lot to me.

Wilson holds a gift from Tara—a lapidary art piece crafted by her father. Photo: Tara Kerzhner

Len: It’s kind of crazy that your connection to Smith Rock more deeply connected you to your own community in this roundabout way.

Tara: Yeah. My dad was adopted, so we were completely removed from our Native family and relatives. I still don’t really know who they all are. So it was really cool to make that connection with Wilson.

Len: So much of our identity is traced back to this thing called blood quantum, which is not a Native concept. Whenever you go into Native communities, they ask you who your family is, first. And of course, Wilson asked you that and knew your family. There is a connection here.

It’s kind of funny that in terms of carrying on a connection to landscape, you’ve done it in your own way through climbing. And I know that was a point of tension in that conversation with Wilson, the role of climbing on this landscape. For you as a Native person, it’s connected you to this place, but for Wilson, it’s something that he views more negatively. Could you talk about his view on climbing?

Tara: I recorded the verbal telling of Animal Village and then we chatted a little bit about climbing because he knew that I was going to be photographing climbing. When I asked him how he feels about the climbing at Smith Rock, he said very strongly that he does not like it, that it hurts the landscape. It’s eroding the earth. He doesn’t like the bolts. He doesn’t like the chalk. And he doesn’t like what it’s doing to the place. And as someone who clips those bolts, puts that chalk on the wall, stomps around on the base of the climbs and contributes to erosion, I felt bad immediately.

I think that the first time I ever heard that Native people didn’t like climbing was when we were talking about Shiprock, so it wasn’t like it caught me totally off guard at all. It was just a strong opinion from someone I respected a lot. I guess I knew that all along leading into this—because one of the reasons I wanted to do this in the first place was because I felt like if non-Native people knew the creation stories, they would fall in love with these places as much as Native folks, or maybe they’d fall in love with Smith Rock as much as I have fallen in love with it. And they would treat it better and be better stewards to the land. So it was coming from a good place of doing this project. But I think as someone who is part of that impact, when he said that, I kind of just took it in.

Tara leading up The Northwest Corner, generally considered one of the best crack climbs at Animal Village. Photo: Jules Jimreivat

Len: I think that’s been one of my learnings as I’ve gotten older. You hear what the Elders say, and it always becomes this question of like, well, what’s better? Is it better if a Native person isn’t connected to a landscape? Do impacts that happen from climbing outweigh the benefits of reconnecting Native people to the landscapes that we’ve been attached to for thousands of years?

In terms of that Elder-to-young-person dynamic, it’s a conversation. Where I’ve come to with climbing and skiing, if I get some pushback from Elders, I’m like, well, had I not done these things, I wouldn’t have learned these ceremonial songs that are attached to these landscapes. I wouldn’t have learned some of these creation stories. And I wouldn’t have been an advocate for protecting these places in the way that I am now. And is that a worse position than we were in before had that not happened? I would say climbing allowed you to reconnect with the landscape and have this conversation with Wilson. And I don’t think he’s ever probably met a Native climber before.

Tara: I definitely think that was a first. And if it weren’t for climbing and photography, Smith Rock would have been a place that I would’ve thought about but wouldn’t have connected to like I did. It would never have led me to learning about the creation story and asking myself the questions of like, is it OK that I have this impact?

Len: Yeah. And in terms of carrying on legacies, you know, Wilson and our Elders aren’t gonna be around forever. It’s our responsibility in many ways to learn the things that they have to teach us, but at some point, we’re gonna occupy that role.

Tara: I think that when more Native people start climbing, this will be a lot different than it is now. In bringing more Native people into these sports, skiing or climbing or whatever it is, you’re inviting different perspectives and a more empathetic view of the land than you might have from someone who literally never had any knowledge given to them about the importance of the land outside of simple stewardship.

It definitely makes me feel like I have a responsibility now, because I know a little bit more than some of my peers in the climbing community. But that’s why I wanna share those stories. Because I think that if people can see this and know how deep the Animal Village place goes and the importance for Native people, I think that that could really change the way that people choose to interact with that place. And maybe through our efforts, can chip off a little.

Len: Yeah, I mean, history and society have so much momentum behind it. The best that we can do is change the course by a degree. But in the same token, climbing’s what brought you closer to understanding your own relationships with land.

This is a very Navajo perspective, and it’s not reflective of all tribes, but I was always taught that everything has good and bad within it. Everything’s a mixture of those two. And whatever comes out or whatever’s prioritized is what will be shown. And I think especially around climbing, my own community has a very tumultuous history of climbing on our sacred rocks. There’s a climbing ban across the res.

Tara pauses on Misery Ridge. Photo: Jules Jimreivat

But what I’m seeing with a lot of younger folks that are starting to climb is that they’re starting to become curious of the landscapes that they’re spending time on, because we’re not sheepherding and doing all these things that traditionally connected us to the land. And I say, well, you know, this has an impact, but I think the impact from Native kids not being connected or Native peoples not being connected to the landscape is a way greater harm than the impacts there. In terms of our lived experiences, there’s some understanding that we wouldn’t be having this conversation had it not been for climbing.

Tara: Totally. I do think that it’s worth questioning yourself as a climber or a skier. It’s an important question to ask yourself, is this OK? And I think that could be that degree change for you, or hopefully more than a degree, at the very least in how you respect the places that you’re recreating on.

Len: Right. I would say the Navajo worldview is not feeling entitled to a landscape.

In sharing this story, you alluded to this a little bit before, but what do you hope for non-Native climbers who climb at Smith? What should they take away from this?

Tara: I think originally it was, look at how beautiful this incredibly in-depth creation story is. Listen to it. Take it in, understand how sacred and meaningful this place is and has always been to Native people, to the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs and other Northern Paiute.

Understanding is part of learning to respect it. Knowledge brings empathy. The more knowledgeable you are, the more understanding you have, the more empathetic you can be to something you may not have understood. If you know how important this place is to Native people, and how incredibly beautiful the story is, it completely changes the way you look at the landscape.

I mean, you listen to what Wilson is saying. In my head, I was living this story in my mind and animating it inside my brain. And knowing Smith Rock so well, and Fort Rock, I could really envision exactly what he was saying. And then I retold it to a bunch of people. Cause I thought it was so cool to connect deeper to this place. I guess my hope is that people will find it as cool as I do—because I think if they do, then it will change the way that they feel about the place.

Len: Yeah. I’m from the desert Southwest. We have big rocks out there, but to hear another story from another place, it felt like an animation. Like I was living in that story. And having spent a little time at Smith Rock, it gave me a deeper respect and understanding for that place. Because quite honestly, you go to that park and there’s not really a whole lot of acknowledgement of Indigenous people. And I feel like that’s a loss for the people that visit because that’s a whole layer of history. Thousands of years of history in addition to the climbing and stuff that’s already there.

Smith Rock local Mira Capicchioni waxing poetic on Time to Power (5.12c). Photo: Jules Jimreivat

Tara: They have these little plaques up there. It’d be sweet if they had one that just said the original name for Smith Rock. I mean, Smith Rock is kind of a lame name in general. And [the name] Animal Village, if you’ve spent any time in Smith Rock, makes a lot of sense. You’re just walking down the river and there’s otters and bald eagles, baby bald eagles.

What I like about the Animal Village is that you immediately recognize how that place is used by the animals [who live there], they’re living off the land. And so instead of a place named after a dude named Smith, you’re immediately recognizing that the land is more valuable than someone’s name. The land is valuable because the animals live there, and they need the land to survive.

Len: It was named after John Smith, who was the Linn County sheriff and Oregon legislator in the 1850s and 1860s. A newspaper article credits Smith with “discovering the rock.”

Tara: Oh, wow.

Len: Another story claims the rock was named after a soldier named Smith who fell to his death from the rock in 1863 while the unit was camped nearby. Whatever it was, I think the name Smith Rock really diminishes the vibrancy of that place.

Tara: It does. I totally agree. I think a lot of places are being renamed these days. I would love to see Smith Rock renamed officially to Animal Village. That’d be so sweet.

Len: Animal Village State Park would be awesome.

Zooming out, we’ve talked about Shiprock and how it led to this conversation about Smith Rock, but there’s a lot of places that have creation stories where we climb and do these sorts of things. Could you talk about the importance of that and what we should be thinking about moving forward?

Tara: Yeah. I think it’s, take this as a lesson for every place that you like to recreate in. And if you’re a nerd like me, you’re gonna start looking up the creation stories for all the places you like going to. There are so many places that we recreate in that have these Indigenous place names stories.

Len: Yeah. Once you get that taste, it becomes really interesting. It’s this whole layer of history that adds a whole new level of depth and curiosity.

Tara: Imagine if history classes just taught Place Name Stories!

Len: “Now we’re gonna have you jug up El Cap and recreate the story of the inchworm.”

Tara: Oh yeah. Jugging up El Cap truly is the inchworm.

Read Legends of the Northern Paiute by Elder Wilson Wewa