One for the Grove

Friendship among the whitebark.

All photos by Sofia Jaramillo

In the cold and dramatic landscape of Northwest Wyoming, a forest ecologist, guide, avalanche professional and true mountain lover roams the high forests nurturing a very important connection. She has been taking care of extraordinary trees in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem for half her life, and she has seen it change during her time in the forests. Nancy Bockino grew up in northern Idaho. Her parents were naturalists and scientists, promoting curiosity and imprinting upon her a powerful love for the natural world. They spent summers living out of a Volkswagen bus in the forests. When she finally found her way to the Tetons in Wyoming, she established a place in the local ecosystems—the alpine forests and the community of people. Her tree work started within a year of arriving. “The trees chose me, not the other way around,” she says to the curious. Trees are her kindred spirits and her teachers of life’s purest ethics: patience, connection, perseverance and flexibility. More than two decades into her relationship with whitebark pine, she sometimes wishes she was “one of the grove and could stay forever, standing in one place listening, feeling, watching and learning.”

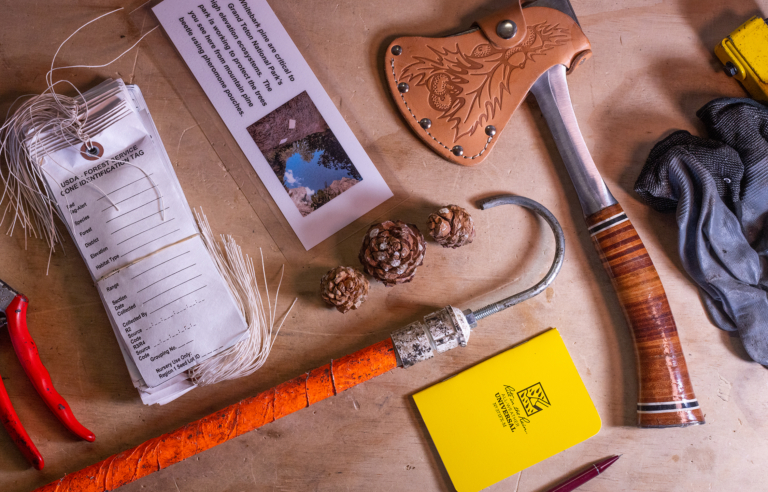

The tools of Nancy’s trade: a cone-caging pole for pulling branches, a stable hammer for hanging verbenone pouches, a hatchet for peeling bark from the trees killed by beetles, clippers for collecting pollen and cone tags for labeling bags of cones.

My appreciation began six years ago when my friend Nancy asked me to replace a retiring member of the team who had been conducting fieldwork for a whitebark conservation program. After the first season, I still couldn’t spot the whitebark all the time. They remained hidden, blending in with the other trees, coming into view only when pointed out to me. It was humbling. When I returned for the second season of work, the trees began appearing—and then, they were everywhere. It was as if I needed to show my commitment, or perhaps my humility, before they would reveal themselves. In an attempt to help a human friend, I’ve now found friends in these trees. Nancy and I are never too far from them, even in winter. Working as ski guides and avalanche professionals, we visit them routinely, showing guests and friends their splendor and skiing their perfect openings. Embraced and surrounded by these ancient giants, we fly through stands of them on fresh snow. And they are always there, adapting without moving, offering lessons to visitors through the grace of their existence. The whitebark are so well suited to thriving in the drama of a harsh environment.

The whitebark are a five-needle pine that can grow to be hundreds of years old. The species is distributed in Pacific Coast Ranges from British Columbia to central California, and in Rocky Mountain ranges from Northern Canada to northern Nevada. It is a keystone species, regulating runoff by slowing the progress of snowmelt, supporting diverse alpine communities and providing a high-energy food source for animals.

This small but mighty cone is key to the survival of whitebark trees and the ecosystem around them. The seeds which it holds are an important food source for many species such as birds and bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

But the hearty and humble whitebark is experiencing a frightening population decline as the temperature scales tip toward warmer and drier conditions. More frequent and intense wildfires, droughts and the spread of beetles brought on by a warming climate pose serious threats to whitebarks. Up to 80 percent of old-growth whitebarks in the Greater Yellowstone area are estimated to be dead or dying after the most recent beetle outbreak between the early 2000s and 2010. Ecologists say rising temperatures are the main cause of this devastating spread. We notice it as visitors to the alpine environment, and we can connect the dots back to a changing climate. Meanwhile, we live in luxury under big roofs where we can simply throw another log on the fire or turn on the AC. But imagine living there, way up high on the mountain ridgetops, and feeling climate change more directly.

Imagine being a 1,000-year-old alpine tree standing in one place season after season, pressing your roots into spaces between rocks until you slowly become the place.

And sadly, the decline is continuing at an alarming rate. Since 2019, the loss of the few remaining old-growth whitebark has significantly increased in parts of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. The nuanced details of this drama include a strangling fungus and a tiny predator. The non-native and insidious fungus, white pine blister rust, has become a significant problem for the whitebark. This blight finds its way in, bubbles up in orange fruiting bodies and strangles the tree’s circulatory system. Rust-resistant genes exist in some populations of whitebark, but they are in the minority. Since the late 1990s, a tiny predator, the native mountain pine beetle, has been given a huge advantage and seized the opportunity. The lack of historic fall and spring cold snaps severe enough to kill the beetles when they’re vulnerable has allowed their numbers to rise.

Left: Nancy’s tree-climbing harness hangs next to a collection of old pitons, hemp rope and tools. Each item is from a special place or person encountered during Nancy and the author’s mountain travels.

Right: Created by local Jackson ski company Igneous, Nancy’s favorite skis are made from wood harvested from an already-dead whitebark pine.

So it comes to this for these grand and majestic trees, the giant prey. Without the cold’s established check-and-balance system in place, the tiny predator destroys the forest one tree at a time. And the giant prey, fighting a strangling fungus and native beetle, serves as a martyr. But have we failed to mention all the characters involved? A quick examination of the plot reveals our involvement. We are stewards of a delicately balanced system, thus far proving ourselves unworthy of that with which we have been entrusted. Ultimately, it is our actions that have distressed the balance so quickly. And yet, we have the power to choose to reestablish this critical relationship.

Choosing to learn the uncomfortable often requires a bridge or connector, an invitation to look deeper. An invitation to feel a little deeper. Unlearning the truths we make ourselves accountable for is more challenging when there is a witness. The whitebark are both connector and witness, helping us stay intimate with the world up high while patiently observing our choices. Because of them, many of us will never see the mountains, or climate change, the same again. Bridging the human and non-human, whitebark allow the mountain visitor to connect to the distinctly harsh and indifferent environment above tree line—the alpine.

Colin Wann (left) and Nancy (right) visit a dead whitebark in Grand Teton National Park. Nancy estimates that this tree is more than 700 years old—over halfway through the healthy life of a whitebark.

Solving the challenge of climate change will require emotional bridges to be built. A relation must be made with ancient beings and the systems they are a part of. That we are a part of. Climate change becomes more relevant when the effects are apparent in the stands and individual trees you know. Silently wailing an alert about their increasingly precarious existence, the whitebark offer an open invitation to meet them. They are up there waiting to introduce themselves. And down below the deep blanket of snow, there are tiny whitebark just starting their long life, if conditions allow.

You should go meet them. You’ll never see the place the same again.