North Shore Betty

After nearly 30 years on the hallowed trails of southern British Columbia, Betty Birrell still thinks life is one big playground—and that you’re never too old to send.

It’s a typical fall day in the forests above North Vancouver, British Columbia. The rain is coming down so hard you can’t see more than a few hundred feet, almost obscuring the cedar trees swaying in the surrounding murk. Wind whips between the column-like trunks, making waves through a sea of emerald sword fern. A crack! slices through the rain as a small tree snaps and falls into a nearby stand of Douglas fir.

If Betty Birrell and her son, Hayden Robbins, are fazed by the weather, they don’t show it. Their bikes seem to float down a river of contorted roots, greasy rocks and slippery wooden bridges as if it’s a mild day in June, with Betty leading through the vilest conditions. It’s amazing to watch. She is much, much more confident on these trails than I will ever be, and I’m half her age—and a former professional mountain biker, though I feel embarrassed to admit it at the moment.

At 73 years old, Betty has called these trails home for almost 30 years. In the early 1990s during her mid-40s, she bought her first mountain bike, and a good friend she refers to only as Old Rob took her down 7th Secret, a trail on Mount Fromme. Her second ride was on the aptly named Executioner, another steep, rooty, technical fall-line descent. Both trails have retained their black-diamond rating, and even on the plush full-suspension bikes of today, most riders would find Executioner terrifying.

Her face lights up at those memories. “I was hooked right away.”

Betty poses at the bottom of Empress, a treacherously steep, extremely technical double-black diamond on lower Mount Seymour. Photo: Jordan Manley

Betty’s entrance into mountain biking—as a single mother a few years short of 50, raising a 6-year-old while flying overseas each weekend as an international flight attendant—is unconventional, by most measures. But to start on Vancouver’s North Shore during the 1990s … well, that’s another level of gnarly. Clinging to the mist-shrouded slopes of Mount Fromme, Mount Seymour and Cypress Mountain above North Vancouver, “The Shore” is to mountain biking what Yosemite is to rock climbing or what O‘ahu is to surfing: Few other places have done more to influence and define the sport. And, like the Dawn Wall or Pipeline, it is not for the faint of heart.

“Some people say that California invented mountain biking,” says local trail builder Todd Fiander. “The North Shore invented mountain biking.”

The Shore’s infamous trails are a cross between a BMX track and an Ewok village, a convoluted web of wooden ladder bridges, rock drops, berms and “skinnies”—narrow, raised features intended to be ridden across. Some of this woodwork climbs into the trees, demanding riders navigate catwalk-like planks, sometimes only 6 inches wide and as high as 20 feet above the forest floor. Other features roll multiple stories down near-vertical rock faces.

Left: Ladies Only is one of Todd Fiander’s most beloved masterpieces, a seminal and lasting testament to his vision and commitment to giving people a good time. He built it in 1992 and has been personally maintaining and tinkering with it ever since. The trail redefined what was possible, with features like the first-ever teeter-totter bridge and the iconic “Monster” roller coaster, and though it’s seen some overhauls over the past 30 years, it still embodies the spirit of those early days. Photo: Jordan Manley

Right: Built by “Dangerous Dan” Cowan, the Flying Circus trail on Mount Fromme represents the absurd pinnacle of the North Shore’s renegade early years. It had the skinniest, highest and most dangerous features anyone had ever seen and could only be ridden by a handful of people. Trails like Flying Circus were decommissioned as mountain biking became more widely adopted, but the remnants speak to the enduring legacy of cedar planks, mad creativity and an unrelentingly desire to push the limits. Photo: Jordan Manley

“Shore-style” trails can now be found across the globe, but when Betty started riding in the early 1990s, locals had only been building them for a few years. Todd—or Digger as he’s known in the mountain bike world—is considered the first to incorporate ladder bridges and raised wooden structures into his trails. He’s observed nearly every notable rider on The Shore for the past three decades and captured many in his 11 North Shore Extreme films, including—to my surprise and, I must admit, chagrin—Betty.

A few years ago, I made a documentary about the history of free-ride mountain biking, much of which happened on Digger’s trails, yet I hadn’t heard of Betty until this past year. I’d seen her, however, while poring through hours of Digger’s grainy camcorder footage. I just didn’t know it was Betty.

“She was the first person to ride The Monster,” Digger says, referring to an iconic stunt commonly regarded as the first “roller coaster.” (It looks exactly as it sounds, just made with slats of split cedar.) “I had just put the last plank down and asked her to ride it for me, so I pulled out my camera and filmed her. The third time, she fell and pulled out her shoulder, and I had to pop it back in. And I think she was like 55 when she did that.”

Betty recounts those early days so casually, it takes me a few minutes to realize how insane her entry into the sport was. In the early ’90s, body armor was rare and full suspension and hydraulic disc brakes were nonexistent, making the bikes as much of a liability as a lack of skill.

“Fortunately, I didn’t really have a fear of falling,” she says. “Still, I was covered with bruises, black and blue. I couldn’t go out wearing shorts because it looked like someone took to me with a baseball bat.”

The North Shore is well-known for its wooden features and rock rolls, but what gets most people are all the roots, which become so slippery after a rainstorm that even a slightly misplaced tire can lead to disaster. For Betty, such greasy sections—like upper Floppy Bunny—just add a little spice to long-familiar trails. Photo: Travis Rummel

But full-send is how Betty operates, under the radar or not. Born in the rural town of Chemainus on Vancouver Island, Betty moved to the city of Vancouver to study geography at the University of British Columbia, where she joined a crew of fellow climbers who got after some of the biggest peaks around Vancouver.

“In the ’70s, she was part of this really hard-core group of climbers that had all sorts of first ascents in the area,” says Hayden, who is a professional ski guide and operations manager for Whitecap Alpine Adventures. “But they wouldn’t claim them because they didn’t want people to find the zones.”

Betty picked up windsurfing a few years later and by the early 1980s had become one of the top female windsurfers in the sport, flying out of huge 30-foot waves the likes of which no woman had done before. As an editor for Sail Boarder Magazine put it in 1982, “Betty Birrell is a superstar of the sport … a leader of the leading edge … ranked on par with most top men.” The German magazine Surf summed it up even more succinctly in a headline from their June 1982 issue, “Betty Birrell: The Best Female Surfer in the World.”

She stationed herself in Hawai‘i, working as an international flight attendant while surfing big waves between shifts. She married a fellow Canadian three years into her time on the island but continued to commute between Hawai‘i and British Columbia for a year so she could sail. Eventually, Betty returned to Canada and, at 39 years old, gave birth to Hayden.

“I think motherhood is the best adventure ever, really,” she says. “I was so surprised how much I loved being a mom, how much I loved being pregnant.”

Just before Hayden’s second birthday, her husband left them. She recalls an argument before the split, “He said, ‘You just think life is just one big fucking playground!’ And I said, ‘Well, yeah!’ I thought it was a compliment.”

Most moms go on walks with their kids; Betty and her son Hayden Robbins session double-black diamonds, which has become somewhat of a family tradition after two decades of riding together. Mother and son scope the final rock roll on Empress before dropping in. Photo: Jordan Manley

As a newly single mom, Betty worked overseas flights on weekends while Hayden stayed with his dad or grandmother, and she’d return for Hayden’s bedtime on Sundays. “You just kind of adapt as you go along,” she says. “I just reinvented adventure. Instead of going mountaineering or stuff like that, we’d go car camping with my parents, and it was just so fantastic.”

Betty’s face glows when we talk about anything mom-related. She asks to see photos of my kids and swoons at the sight of them. Above the stairway in her home is a huge photo of her and Hayden beaming after a day of cat skiing together.

“Mountain biking was the perfect activity for a single mom because it was right outside our door and easy for [me and] Hayden to do together,” she says. “I would pick him up after school, and we’d dash over to Fromme for a ride.”

Hayden remembers her enthusiastic coaching and patience on the trail. At an age when most kids want their parents to park around the corner to avoid being seen by their friends, Hayden welcomed his mom joining him and his friends on rides. “It’s amazing when you get on a technical trail with her,” he says. “She just zips along like you wouldn’t believe. She’d be better than my buddies, so that was a funny dynamic.”

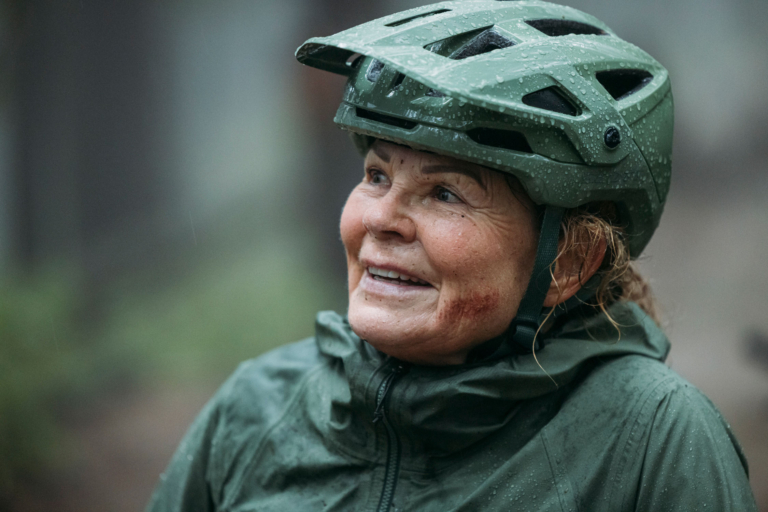

There’s a price for riding someplace as high consequence as the North Shore, and it’s one paid in smashes, scuffs and oftentimes broken bones. On this particular afternoon, neither the weather nor a bruised jaw could wipe the smile off Betty’s face as she sessioned the black-diamond Pingu trail on Mount Seymour. Photo: Travis Rummel

Let me just say that if my mom were mountain biking alone down double-black diamonds, I would probably give her a tracking device or an emergency beacon. But Betty isn’t my mom. And I’m not Hayden. “My concern for my mom is overridden by knowing she is so experienced,” he says. “She is the consummate mountain woman.”

Some people, however, notice her age before her ability. Occasionally, she notes, when coming upon fellow riders assessing stunts on the trail, “They see I’m older, and I’m a woman, so they just stay in the way because they think I’m not going to be able to ride it. I just say, ‘Excuse me, I think I’m going to ride on through.’ I actually like that because I feel like I’m doing a service for women—older people, too, but especially for women.”

But with all sports, injuries happen. Like that time she broke her leg hard-boot snowboarding. Or when she broke both her hands riding the infamous Rippin’ Rutabaga rock drop in the Whistler Mountain Bike Park in 2003.

“I remember lying on the ground,” she says. “I was 54 then, and I knew I was hurt badly, but I didn’t want to tell the bike patroller how old I was.”

Hayden was 15 at the time and returned home to find his mother immobile from the shoulders down. “She had these crazy wrapped arms, lobster-claw things,” he says, “and she couldn’t do anything.”

At age 58, Betty took early retirement and started her own landscaping business; she still helps friends and family with their yards occasionally, though no longer as a profession. These days, she mostly rides alone: Most of her bike buddies work during the week, and Betty avoids riding on weekends (the trails are too busy, she says).

And, of course, she still rides with Hayden whenever he’s home. Hayden now lives in Revelstoke, British Columbia, and whenever he talks about his mom, he’s visibly proud. “For me, she’s laid the path that I’ve followed in my life, and it’s a different path than a lot of people,” he says. “But she’s always been the biggest supporter and inspiration.”

In a place that can receive 100 inches of precipitation each year, you get used to riding in the rain; after nearly 30 years, Betty actually enjoys it. Betty and Hayden navigate roots and the weather on lower Pingu—just another lovely day on the North Shore. Photo: Travis Rummel

Almost 30 years after her first lap down Executioner, Betty admits she’s scaled back her riding (she avoids skinnies in particular), aware that a bad crash could have larger consequences than when she was younger. But she still sends. Not because she’s fearless. She just knows better.

“It is calculated,” she says. “You know your limits. Sometimes you push a little bit too much and you get away with it. But you know your limits, and you know what you want to do.”

Back in the fall storm, we call it a day and say our goodbyes. As I pull out into the pouring rain, I’m left with an overwhelming sense of permission to try all those things I’d convinced myself I was too old for. I’m not aging out of the fun and games of my early 30s; after a day with Betty, I feel like the good times are just beginning.

“When I was 50 years old, I never thought I’d be able to ride a mountain bike fast down a trail at 73,” she says. “It’s interesting how your perception of age changes as you get older. I would love to be 65 again. Isn’t that crazy? Who would have ever thought. The biggest thing I’ve learned is to appreciate where you are.”