No Pressure

Sometimes releasing the need to summit is what gets you there.

All photos by Alexa Flower

We trudged downward then upward through the wind and darkness, the Milky Way curving overhead like a swath of ribbon. I wobbled with fatigue as my feet skittered on loose stones scattered across the steep incline. Temperatures were below freezing, but I was drenched in sweat. Before we started walking, I had wrapped a climbing rope around my body like a backpack, and now I felt locked in too many puffy jackets, gasping for air with each labored step. After a few more strides, Rhiannon Williams and I sat down on a flat rock to catch our breath.

“I haven’t been this exhausted in my life,” I lamented.

Huh, I thought, that can’t be true. Yet the exhaustion I’d experienced in the past from many arduous climbing days, nights-long shiver bivies and multiday wall climbs didn’t seem to compare to my current state in the glaciated mountains of Peru’s Cordillera Blanca. I laughed a little, appreciating how the suffering I’d stomached in previous excursions had faded from my memory like a dream.

We’d been searching for the cave where we’d stashed our food, water and sleeping gear. At 15,500 feet, the night was too cold for us to wait until dawn. We needed to find that cave.

We skidded down a loose boulder field, then scrambled up it again. Our headlamps—fully charged in the hours before dawn—now barely illuminated the ground beneath our feet.

“I feel like the cave is below us,” Rhiannon said.

“Maybe it’s above us?” I replied.

We peered at each dark boulder surrounding us. Each looked like our cave; none of them were.

“Let’s hike back to the base and find the start of the route, then follow the trail from there,” I said, feeling queasy after hearing my thought aloud. I wanted to cry, but our conversation kept me afloat. We bantered about how long we’d been awake, laughing at how the boulder could be 10 feet from us, but we couldn’t see past 3 feet. If there’s any climbing partner I was OK getting lost in the mountains with, it’s Rhiannon.

Rhiannon soaks up the sun and wind at our base camp breakfast nook at La Esfinge. Cordillera Blanca, Peru.

Having spent years on big walls in Yosemite, I embraced the ethos of going fast and pushing hard. It felt empowering to do Zodiac in a day on the first all-female team and climb other lines that I once thought would be impossible for me. Yet I also found my self-esteem getting tangled up in my climbing performance. The pressure to climb big routes along with the intensity of my work with Yosemite Search and Rescue, which sometimes means helping visitors on the worst days of their lives, started to overwhelm me. I wanted to push beyond my comfort zone, but more importantly, I wanted to be able to listen to myself when the right decision is to abandon the summit and go down.

The steep approach in the Quebrada Paron (Paron Valley) just as it flattens out, giving us our first glimpse of La Esfinge.

Yosemite Valley is also where I met Rhiannon. We got to know each other on rest days spent lying in El Cap Meadow and sharing stories at community dinners. As a watercolor painter, Rhiannon has learned to appreciate the process rather than the result.

“You can enjoy the experience as a whole,” she told me. “Each painting is part of a bigger picture. Even if you completely paint over a version, it is part of where you will eventually arrive.”

We talked about how climbing can be similar. We were excited to push ourselves, but to value climbing for more than the summit means appreciating the whole experience. Instead of pushing yourself to achieve, it means pushing yourself to grow.

When Rhiannon mentioned that she was looking for a climbing partner for her upcoming trip to Peru, I changed my summer plans and booked my flight a few weeks later.

Rhiannon had her sights on the Original Route on La Esfinge (The Sphinx) (5.10d R): a 22-pitch climb that weaves along the left side of an imposing 2,000-foot buttress. We were both experienced big-wall climbers, but our partnership had been limited to bouldering and cragging. Our one attempt at a multi-pitch route together on El Cap had been thwarted by a snowstorm. This was also our first trip to the Cordillera Blanca, and we had yet to rock climb over 14,000 feet. We embraced a “no pressure to summit” mentality to allow things to unfold organically.

Rhiannon navigates the upper pitches on La Esfinge.

We planned to fix a pitch or two on day one, then descend to the ground and spend the night in a cave before pushing on to the summit the following day. The first 10 pitches consisted of difficult climbing, but it would be easy to navigate with cracks, chimneys and occasional bolts. The second half of the route followed seams that were too shallow for gear, with bouts of unprotected slab.

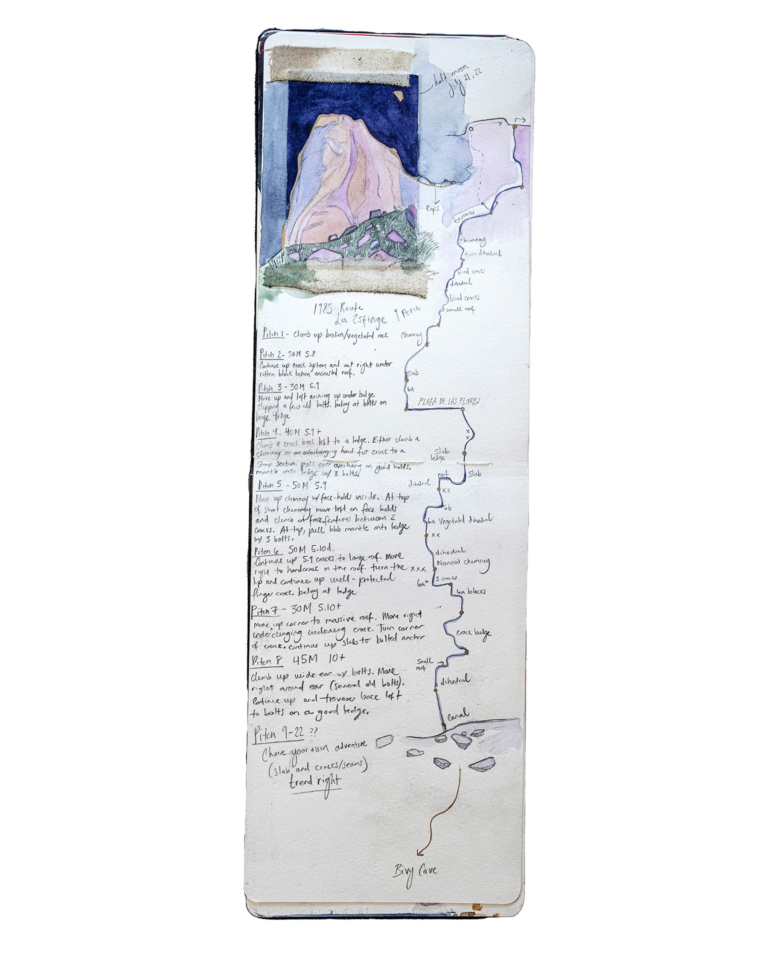

As a watercolor artist, Rhiannon finds inspiration in the landscapes she climbs. “I painted this the day before climbing La Esfinge,” she said. “Something about the act of painting a topo helps to calm the jitters and familiarize myself with the features of the route.” Photo by Rhiannon Williams

“Route-finding is the crux from there,” friends around town cautioned. “Follow your nose and find the most accessible terrain.”

On the approach to base camp, we encountered several parties who warned us about the climb. They asked if we were taking the route seriously, offering ominously detailed beta. Soon I avoided anyone on the trail, as they surely would stop, look grimly at the cirque shimmering in the sun and warn us about La Esfinge.

We needed to acclimatize before trying La Esfinge, and Yanapaccha (17,913 feet) seemed like a good opportunity to practice some snow climbing, too. Rhiannon and our friend Jane Horth get ready for the first of two attempts of Yanapaccha.

That evening, we nestled into our bivy cave, and I spooned rehydrated pesto risotto into my mouth while the wind howled outside. We peered out and saw headlamps high on the wall well past dark. I shivered, partly from the cold and partly from the apprehension, and burrowed back into my sleeping bag. Earlier conversations with the other climbers echoed in my mind. Were they warning us because we’re an all-female team, or is the route really so dangerous? Before bed, we devised a plan to retreat if things felt too dicey, and I let some of the pressure fall away into the wind.

By sunrise, we ascended the rope we’d fixed the day before. Rhiannon put me on belay and I cast off. The rock felt solid, with small, textured holds interspersed between long, wide cracks. At times the route followed steep dirt and vegetation clinging to the granite. I stepped hesitantly onto the dirt “steps,” wondering if everything would rip off the wall under my weight. The high altitude demanded small, calculated movements—if I moved too quickly up a chimney, I’d see stars. By midday, we rested on a flat bivy ledge at Pitch 11, which was filled with small bushes of tiny flowers and aptly named Repisa de las Flores (Flower Shelf). This was our last opportunity for an easy retreat.

We weighed our options as we gazed up at the next pitch: a clean, continuous corner leading into a sea of unprotected slab. This was Rhiannon’s lead. Away from the noise of other people’s opinions, the moment felt light. It wasn’t that we needed the summit. We were excited to push ourselves, curious to see what the rest of the route demanded.

Rhiannon clipped the lone piton protecting the airy traverse and crept upward.

As expected, our pace slowed on the blank, barely protected face as we searched for signs that we were still following the established route. The sun knelt behind a ridgeline by midafternoon and temperatures plummeted. We raced the oncoming darkness, topping out the final pitch at dusk. The cold pierced our layers as we danced to celebrate and keep warm. The snowy peaks came to life around us in the moonlight. We embraced and beamed with joy and relief before hustling down to the rappel stations.

We started our descent in the waning light of our headlamps.

A steep labyrinth of glacial ice smooths out into a pristine headwall on Yanapaccha. Rhiannon and Jane hike up.

Although the thought of hiking back to the start of the route had nearly brought me to tears, the decision ended up being a good one: Our boulder and cave emerged soon after we found the vague climber’s trail that had eluded us earlier. I sighed as I crawled into my sleeping bag, flattened by the heaviness that had amassed throughout the day. I heard a hiss and a small whoomph as Rhiannon lit the Jetboil to make tea. Too fatigued and achy to eat, I faded into fitful exhaustion.

Early the next morning, we ate oatmeal and slowly packed our things. We talked about the climb on our hike out. Ironically, the lack of pressure to summit helped us summit. With open communication and no expectations, we moved with ease because we trusted the process and each other. With bailing as an acceptable option, I found it easy to listen to myself and let go of perfectionism. It felt like a step toward how I want to interact with the mountains and the type of climbing partner I aspire to be.

Our ascent didn’t fall into that familiar, aggressive need for a summit, but rather it let the day unfold without the pressure of how we thought it needed to go. Having our motivations in the right place made for a more joyful, honest climb. If Rhiannon or I wanted to go down, we would have done so with a smile.

At our backs, La Esfinge glowed in the morning light. We headed on our way.

On our first attempt on Yanapaccha, as we acclimatized for La Esfinge, Rhiannon, Jane and I decided to turn back less than 500 feet from the summit because our pace was too slow and the snow was getting too soft to continue safely. Still, we were happy about what we had learned on the attempt. A week later, Rhiannon and I tried again—with our newfound skills and a faster pace, we reached the summit on a crisp, calm morning.