An Expedition on the Latok Northwest Face

The incredible northern aspect of Latok I (~7200 meters) needs no introduction as one of the world’s greatest unclimbed mountain escarpments. Since the historic first attempt by an American team in 1978 (still holders of the current highpoint), the peak has seen more then 30 unsuccessful expeditions. Although it has been climbed once from the south, via a serac-threatened snow route in 1979, an ascent from the Choktoi Glacier remains one of the greatest challenges in the Karakoram.

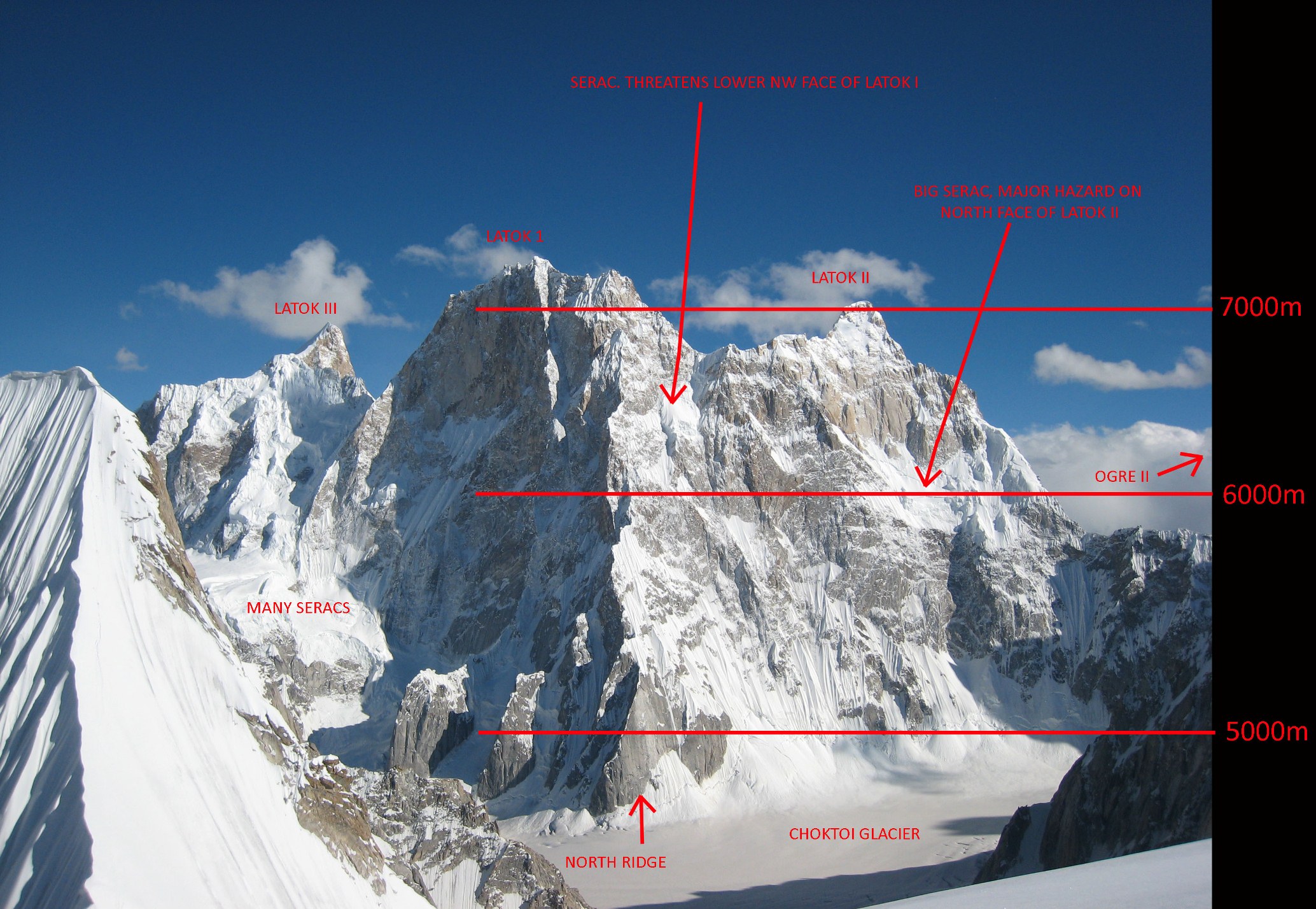

Latok I and II, showing the infamous North Ridge outlined by the sun-shade line dropping from Latok I’s west summit. The lines show possible routes of ascent. The lower 500 meters is blocked from view by a smaller peak in the foreground (outlined in black for clarity). From the final bivouac (marked by a small white triangle), we will traverse easy snow slopes along the South Face to the summit, before reversing our path of ascent.

I first became infatuated with Latok in 1998, at a small slideshow by the accomplished American alpinist Jeff Lowe, a participant in the 1978 expedition. I felt the mountain was the best combination of aesthetics and difficulty that I’d ever seen, and dreamed of one day being capable of climbing it in alpine style. By 2007 I felt I had gained the requisite skills and experience, and made my first expedition to Latok. Completely shut down by poor weather, I returned again in 2008 and 2009. On each trip, my partners and I were thwarted by weather, conditions, or both.

I have now spent more then six months of my life camped below Latok I’s north side and feel I have begun to understand its various moods, and why it routinely defeats some of the world’s best alpinists. The commonly attempted North Ridge harbors huge snow mushrooms which are generally made of bottomless sugar snow. The ‘78 Expedition – climbing capsule style in July over a period of 28 days – experienced a particularly dry snow year, obvious by comparing photos from many expeditions. Nearly every expedition since ’78 has been defeated by poor snow conditions. It’s my feeling that global warming, and increased snowfall in the Karakoram, has made the North Ridge impassable without a sustained siege attempt. In 2009, I ventured onto the North Face proper, optimistic that it offered a less conditions dependant, albeit more technically difficult, route to the summit. Unfortunately, I learned that falling debris, coupled with unprotectable vertical terrain make an alpine style ascent ridiculously difficult, if not impossible.

After three years of struggle, I feel the solution is to climb the Northwest Face, gain the col between Latok I and Latok II, and continue along the South Face to the summit. This line offers the most reasonable terrain, completely avoids the North Ridge mushrooms, and leads to what is sure to be good snow on the South Face. In fact, in 2008 and 2009 I used the lower portions of the Northwest face to reach the North Ridge at approximately 6000 meters, and found the climbing moderate and straightforward. Using this approach we were able to reach previous teams’ second bivouac on the North Ridge in 8 hours!

Another view of Latok. We will skirt the serac on the Northwest Face to the left or right, depending upon conditions.

So why has the Northwest Face not been attempted before? The answer is a huge serac that threatens the lower two-thirds of the face. Yet, after three trips to Latok basecamp, I have never witnessed significant icefall from the serac. I think the Northwest Face is reasonably safe, and presents an excellent opportunity for a rapid ascent. Nate Opp and I hope that an absolute minimum of equipment, and my detailed knowledge of the peak, will see us to the top in a three-day alpine-style ascent. Despite three failed expeditions, Latok is a challenge that excites me like no other climbing project, and I feel confident that this year’s new approach finally gives our team a real chance for success!

We just received a sat-phone call from Josh and already things aren’t going as planned. But the calvary has arrived – Hayden Kennedy and Kyle Dempster, fresh off their first ascent of K7’s East Face – and now they’re just waiting for the weather to cooperate.