One Thru-Hiker, Many Layers: Jacket Technology Through the Years

In 1974 a friend and I celebrated our high school graduation by hiking the Pacific Crest Trail from Mexico to Canada. Of course we weren’t suspect of our gear at the time, but looking back I can’t believe how much of it was really ill-suited for the job. Near the top of that list was rainwear. For those of us who remember the pre Gore-Tex™ era, it’s hard to believe that urethane-coated nylon was really all we had to keep dry back then. (Well, there was Foamback, but that’s a whole other story).

Because it was the lightest raincoat I could find, I took a Trailwise Coated Anorak (if you remember Trailwise, you’re really dating yourself). I often wondered as I plodded along in the rain if I would be drier if I just took it off. But since this was also before Capilene® and even polypropylene, I was wearing the uniform of the 70’s hiker: a cotton t-shirt and jeans. Getting those things wet was something to be avoided at all costs.

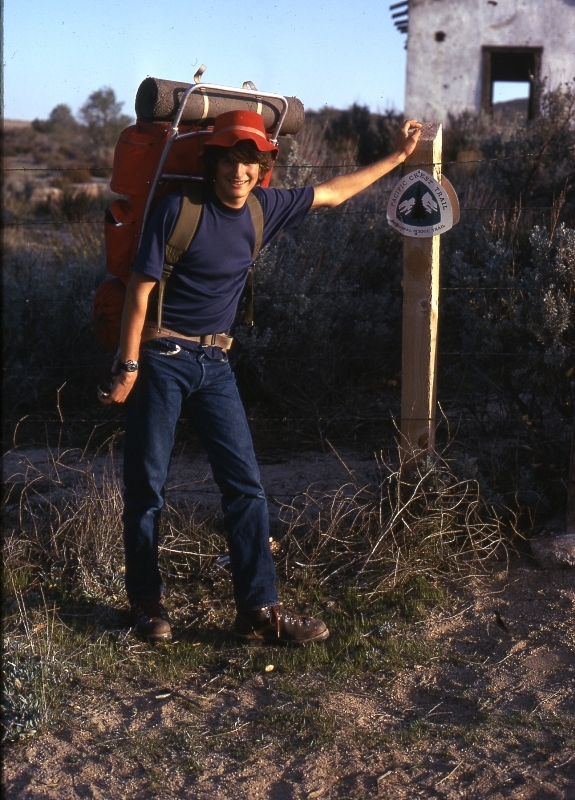

Not-So-Old-School getting ready for the hike of a lifetime. Photo: Old School

Just 3 years later in 1977, my PCT partner Tony and his brother Jon set off on the Continental Divide Trail. They were the proud owners of perhaps the first incarnation of the Gore-Tex™ shell, The Early Winters Gore-Tex™ jacket. After they finished I asked what they thought of this new fangled Gore-Tex™ stuff.

While light-years ahead of my coated anorak, Tony and Jon agreed that this early Gore-Tex™(now known as First Generation Gore-Tex™) was the first step toward something that would eventually change the way people dressed for the outdoors. Among the early problems they experienced were issues with the construction and the fabric itself. This was in the days before factory seam-sealing, which meant whenever you bought a new rain jacket you spent an evening or two with a tube of seam sealant carefully sealing each and every seam. Jon and Tony dutifully sealed every seam but to no avail; both said that water poured through the seams like they were sieves.

Cruising the North Cascades. Photo: Old School

The other problem was a little more mysterious, and had to do with the fabric. Gore-Tex™, both then and now, is made from expanded PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene, think stretched-out Teflon™) that is glued onto the jacket’s outer fabric, usually a more durable material such as nylon or polyester.

In the lab, first generation Gore-Tex™ was wonderful stuff; super breathable, totally waterproof. In short, it was a backpacker’s dream come true. Only in the field did things began to go awry. It turns out there was one thing nobody thought of: when body oils and sweat came into contact with the PTFE laminate the PTFE became altered in such a way as to be rendered, well, not waterproof. WL Gore went back to work and soon had a solution; a very thin layer of polyurethane was laminated onto the PTFE layer, creating a barrier from oil and sweat. It worked. While the addition of the polyurethane layer did reduce the breathability of the fabric, it accomplished the more important goal of preventing the debilitating contamination of sweat and body oils. Factory seam-sealing took care of the seam leakage and by the early 80’s, Gore-Tex™ was synonymous with waterproof-breathable fabric.

Thirty years later, Gore-Tex™ is no longer the only game in town. It has lots of competitors, from eVent™ to Hyvent™ to PreCip™, to our own H2NO™. No longer is being simply “breathable” good enough. With all these new fabrics in existence, fabric designers needed a way to compare and quantify just how breathable these fabrics really were. The measurement they developed is called the Moisture Vapor Transfer Rate (MVTR). While MVTR is one of those terms some tech weenies love to throw at you, most of us have no idea what it means. But if you’ve ever asked how breathable a jacket is, what you’ve really asked is “what is the MVTR of the fabric in this jacket?” This is an important measurement, and as it turns out, not an easy one to make.

MVTR is generally given as Xg/m2/24 hours, where X is the amount of water in grams passing through the barrier per square meter of fabric in 24 hours. And while it sounds pretty straight forward, if you have ever called us and asked for the MVTR (or, more likely the breathability) of any of our fabrics you were probably told that we don’t give those numbers out. Someone might have even said that those numbers were proprietary. While it’s true that we don’t give the numbers out, it’s not so much that they’re proprietary. It’s a whole lot more complex than that. Randy is the man in charge of Quality Assurance for Patagonia so I went to him for a more detailed explanation of why we keep these numbers so close to our chest.

It turns out that obtaining an accurate MVTR is incredibly difficult. When Patagonia first decided to test the breathability of our fabrics, we chose six different fabric labs around the world and sent off a piece of fabric cut from the same bolt to each lab. When the results came back it was both disappointing and enlightening. All six results were substantially different, so much so that you’d have sworn they tested different fabrics. The Quality Team then went one step further; they took the exact same piece of fabric and sent it back to the exact same lab to be retested. Wouldn’t you know it, the second laboratory tests did not reliably match the first set. Obviously, if independent laboratories couldn’t provide similar results from the exact same fabric, comparisons between different fabrics (and brands) were impossible. This discrepancy is the reason we don’t publish hard and fast numbers; any comparison with other fabrics would be meaningless. Anyone picking a product based on one published number is putting a lot of faith in a marketing team and an unknown lab.

MVTR test machine. Photo: RJ Hosking

Nowadays, a budding outdoor clothing company can barely hang their shingle before the door is beaten down by fabric reps, plying their wares. But back in the early days of Patagonia when outdoor fabrics were hard to come by, off-the-shelf fabrics were often the only thing available (the fabric for the original Patagonia Pile Jacket was being sold as material for toilet seat covers). So, we’ve always tested fabrics ourselves in our own Fabric Lab.

Disappointed by the MVTR results of commercial testing, Randy and his team came up with a solution: they made their own machine. Randy explained to me how it works but to tell the truth all I remember is that it involves fans, humidity, thermometers and exacting measurements. This machine gives results that are accurate, and more importantly, solves the elusive repeatability problem that plagued the other labs. Our team was not alone in being impressed with the results; a few of the labs we originally used have even sent engineers to our Fabric Lab in Ventura to see how they did it.

Today, our Fabric Lab team uses this machine to test not only our fabrics but those of our competitors as well. Every fabric we use (or don’t use) has gone through this and many other rigorous tests. Again, while we believe our MTVR test to be accurate, comparing our results to those of other labs will most certainly be meaningless.

It is important to note that Patagonia does not just rely on lab tests when picking fabrics. We also have a whole team of product testers, both formal (the pros, 1, 2, 3) and informal (the rest of us, 1, 2, 3) who give new fabrics and designs the real test. How waterproof and breathable are these fabrics really?

We believe that this combination of lab and real world tests gives us the best performance in the industry, but the more important test is you. What do you think? Let us know. We can’t pay you to try our stuff but we love getting feedback and we promise to listen. Your comments play a major role in our new and redesigned products.(1)

Celebrating the end of a long walk . . . in jeans. Photo: Old School

Celebrating the end of a long walk . . . in jeans. Photo: Old School