Floating Lines

Witnessing the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge via pack raft.

All photos by Andrew Burr

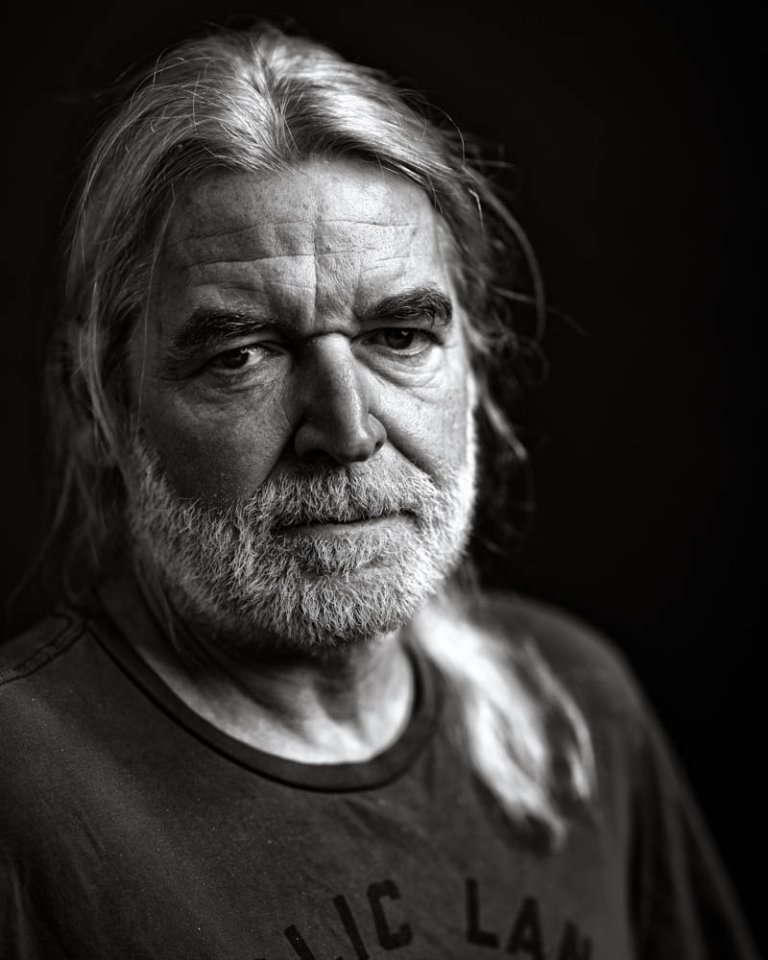

In August 2024, anglers Thad Ferrell and Sarah Tescher joined photographer Andrew Burr to float 45 miles of the lower Kongakut River in northeast Alaska. Traveling light, the trio stopped only to camp, cast to the river’s wild Arctic char and grayling, and photograph the vast landscape of mountains, foothills, tundra, coastal plain and rivers. Flowing entirely within the roadless Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the Kongakut makes its way north before emptying into the Arctic Ocean. The Arctic Refuge is located on the ancestral lands of the Gwich’in and Iñupiat peoples. The Gwich’in call this area’s coastal plain “the sacred place where life begins.”

At 19.6 million acres—about the same size as South Carolina—the Arctic Refuge is the largest and one of the most remote national wildlife refuges in the United States. The 1980 Alaska Interest Lands Conservation Act created new hurdles for exploratory drilling and oil production within its boundaries, requiring congressional approval and the completion of an environmental impact study. This left the door open for Republican administrations to try dozens of times to allow oil production in the region. Today, that threat is real again.

As President Donald Trump ran for re-election last year, he frequently parroted Sarah Palin’s catchphrase, “Drill, baby, drill,” promising that, if elected, he’d open the Arctic Refuge to drilling. He claimed its oil deposits were as big or bigger than Saudi Arabia’s, saying, “I’ll get it going very quickly.”

And he’s trying. On his first day back in the White House, he signed an executive order to open the Arctic Refuge to oil and gas drilling. Trump, who has called human-caused climate change a “hoax,” is wrong about the size of the region’s oil potential; it’s estimated to be less than 7 percent of Saudi Arabia’s vast deposits. He may also be wrong about demand. The last time the Bureau of Land Management held an auction for oil and gas leases there, it received zero bids.

Originally, this assignment was meant to photograph one of the planet’s last remaining untracked, unspoiled masterpieces. Now, however, these photos are a clear call to action and a stark reminder of what’s at stake.

Andrew Burr: This is from the top of a cliff. I was constantly in and out of the boat trying to get vantages you don’t see on the river level—also to look for fish. You could see them because the water is so clear.

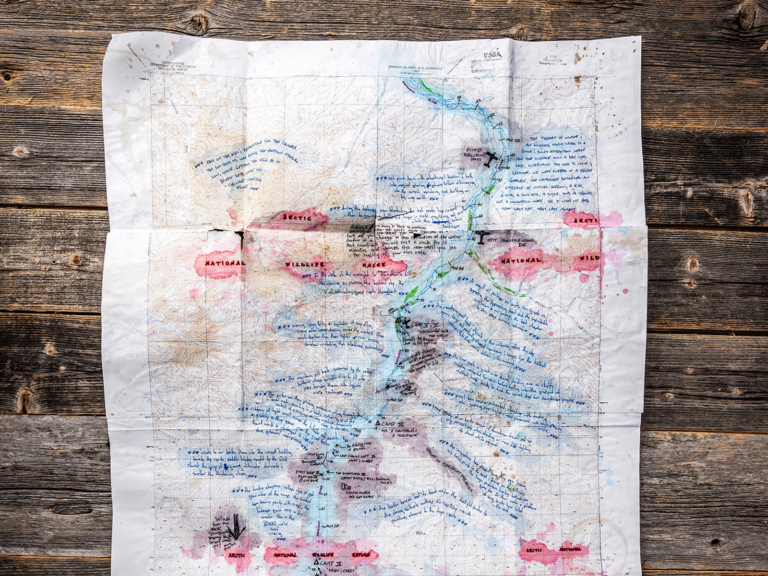

Left: Thad Ferrell adds a note to the group’s map. Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska.

Right: Sarah Tescher on a post-fishing hike.

Thad Ferrell: During the lead-up to the trip, I had this crazy fear that I would totally forget how to fish. Once we got there, I just felt so focused, anxiety-free and like I was doing what I was supposed to do. It reconnected me to fly fishing.

Sarah Tescher: The wading was harder than it looked because the water was so clear. You wouldn’t think it was very deep, but if Thad had taken one more step there, he’d have been up to his waist.

Thad: This was some of the funnest water on the trip. It wasn’t scary—but you didn’t want to swim because it was cold. As we were scouting the water, we saw a group of mergansers. They spotted us, then peeled out and ran the rapid in front of us. You’d think they’d fly over the rapids, but they were just having fun.

Sarah: This day wasn’t crazy cold, and the adrenaline is so high in a white-water backcountry situation that you don’t notice anyway.

Andrew: It’s four topo maps stuck together. I got the other guys to make notes on it, too. I was trying to journal the feeling of each day—the feeling of the area. I touched it up with the colors afterward.

Thad: This was tricky wading. You could get into trouble really quickly. There were many braids, and the main braid was over our waists. We didn’t want to go in because we were wearing every stitch of clothing we had. I was totally focused at that moment. I was looking for that one big fish.

Andrew: These guys spent a lot of time walking, trying to find fish. They were working. I didn’t fish because behind the camera is my happy place. But I love it when someone is so dedicated to their craft that they put on blinders and just go for it.

(Left) Andrew: We wanted to get a view of the fishing coming up to look for runs we wanted to fish. This would be the typical terrain when we’d go for little hikes. It snowed on us on this hike.

Thad: Getting a different perspective on the landscape really cements the enormity of the landscape into your head and your heart.

(Right) Sarah: We mostly caught females, but that looks like a male. The females had red lipstick—beautiful fish with bright red lips. Females were more colorful and chubbier, and males were more sleek and bigger overall.

Andrew: They all looked big to me. When they fill the net up, I call it good.

Thad: This makes me feel immensely small but lucky to have been in that space.

Sarah: No way should a pipeline go through here. I was wondering if we should have even been there. It’s a special place, and I may never be there again, but that’s OK, I’ll leave it for the caribou.

(Left) Sarah: If you get the inside of your tent wet, all your stuff gets wet. I was trying to set up the tent with the rain fly over it so everything would stay dry. Had I waited 20 minutes, I would have had a clear window.

(Right) Andrew: Nothing pretty about that. That’s real camping—pretty much everything we had with us.

Thad: We drank a lot of coffee, played a lot of cribbage and solved a lot of the world’s problems.

Sarah: I caught grayling here. I saw a fish jumping and I switched to a dry fly. I caught three. It was a size 8 Royal Wulff. I probably caught 80 percent of my fish on a Royal Wulff. My dad passed before this trip. The Royal Wulff was his favorite fly.

Thad: This puts me at ease. I can’t think of a happier place. We pulled some nice fish—some big fish—from that run.