On the Vulnerable British Columbia Coast, Looks Are Deceiving

If you’ve ever read a story about surfing on the Canadian coast, you’re pretty sure to have read a few boilerplate paragraphs about how pristine it is in this part of the world. How bears and wolves stroll past the tent sites on the shoreline, perhaps, or how the lineups are alive with seals and whales, or how the water is a pure psychedelic green and the mountains are a thick shag carpet of trees.

Those things are true enough – in the town I live in, you can cast off the rocks for dinner or walk into forests that haven’t changed since the Pleistocene. But those things are also a bit misleading, or at least only partly true. The British Columbia coast has managed to retain much of its beauty and biodiversity, but it’s not some sort of pre-industrial idyll that’s free from the pressures of the modern world. It’s all a matter of image, I guess – you’ll find plenty of text in the surf and travel magazines about our area’s natural attributes, but not a lot about fish-farm waste, or the spawning streams clogged with logging debris, or the fact that Tofino, which bases much of its economy on surfing and eco-tourism, pipes its sewage straight into the waters of Clayoquot Sound. The reality of it is that the coast here is as vulnerable as anywhere to the forces of environmental degradation – the Northern Gateway is one of the more worrisome examples, a controversial pipeline project that would increase tanker traffic and put the Great Bear Rainforest at risk.

No place is a place apart, and probably the clearest illustration of our connection to the world at large is the amount of trash that washes onto our shores. Hike along any one of the backcountry beaches, and you’ll find that you’re stepping over all sorts of garbage, most of it plastic, mixed in with the piles of driftwood and seaweed that mark the high-tide line. Most of the trash on the beaches here floats in from far away, carried by the currents, and seeing such a sparsely populated coastline strewn with garbage is a pretty strong indicator that our species is still treating the ocean as a giant garburator. As Kyle Thiermann notes in this video about single-use plastics, there is no away.

On a note of personal disclosure, I’ve been making a living from writing about the Canadian coast, often as a copywriter in the tourism industry, since I graduated from university a decade ago. In the last few years, though, I started to realize that I wasn’t doing enough to protect the coast that I loved – I was profiting from it without giving enough back in return. I hadn’t been doing anything to cause direct damage, but I was awakening to the fact that my life had become too passive – and in being too passive, I’d become, in effect, a willing participant in the same systems that are slowly but surely degrading wilderness areas all over the world. That realization did some tough things to my spirit for a while, but it forced me to relearn something I already knew: if you want to be effective, and if you want to preserve what’s around you, you can’t just think and talk. You have to act. You have to get your hands a bit dirty, and you have to start with a few steps, even if they seem almost hopelessly small. You have to feel that you’re trying, that you’re doing what you can, or eventually something is going to get damaged inside of you. As Edward Abbey wrote, “Sentiment without action is the ruin of the soul.”

For me, one of those small steps was starting to attend some of the coastal cleanup projects organized by the Surfrider Foundation. The Foundation has a small presence here in Canada, but the Vancouver Island chapter is a gung-ho little group that does a lot of good work to mitigate human impacts at our surf beaches. Even a single day with a handful of people picking up bottles has a measurable result – on a practical level, you’re working to improve your immediate environment, and on a symbolic level you’re showing that you’re not going to give in to the forces that are making our planet dirtier and less diverse. Leave No Trace is a fine philosophy when you’re in the outdoors, but sometimes you have to go beyond that and put in some work to make your land better.

That all being said, I was pretty eager when my friend Lucas Harris called and said that Surfrider was planning a cleanup on one of the remote, roadless islands north of Tofino. This year marks the 100th anniversary of BC Parks, and as the cleanup would be taking place within the boundaries of Flores Island Marine Park, Lucas had been able to secure a government grant that would cover the expenses of the trip. The Surfrider chapter was launching a campaign called Combing the Coast, he told me on the phone, and this would be the first of a year-long series of wilderness cleanups. The Canadian Coast Guard was also planning to support the trip, offering to transport us to Cow Bay and bring our crew and our cargo of garbage back to Tofino a few days later.

It was a warm(ish) spring afternoon when we piled into one of the Coast Guard’s rigid inflatables for the trip to Flores. One of the major islands in Clayoquot Sound, Flores is a mountainous landmass twice the size of Manhattan, the majority of which is untouched old-growth forest. Ahousaht, a First Nations community of around 900 people, lies on the east side of the island; the west side is uninhabited and sees little in the way of human traffic, other than a few kayakers and a few hikers on the Wild Side Trail. After being dropped off in a sheltered corner of Cow Bay, we settled in, set up our tents and went for a surf in shoulder-high beachbreak before turning in for a sleep.

Kelsey and Cori at the Tofino Coast Guard station. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

A juvenile bald eagle in front of camp. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

Post-surf rinse off in the river behind camp. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

Cori tending to the important task of taco preparation. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

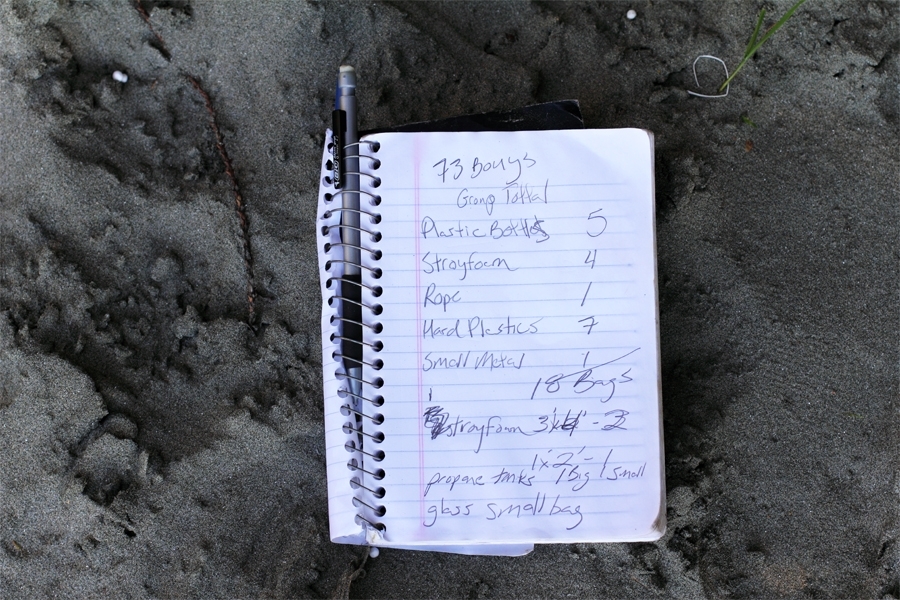

The next day, we split up and went separate ways along the shoreline, walking along the white sand with packs, ropes and garbage bags. A few hours into the day, the physical movements became almost trancelike in repetition – take a step, bend down, pick up a piece of trash, stand up, take another step, bend down again. It was a bluebird day and the work was good for the soul, but it was sobering to see how much garbage there was on a wilderness beach – construction waste from Russia, water bottles from Malaysia, food packaging from Japan. There was also plenty from closer to home – oil cans, fish totes, juice bottles from the Co-op and thousands of water bottles and empty cans of beer. All of it, of course, in the process of being dismantled into tiny pieces by the weather and the waves. There were bigger artifacts as well – propane tanks, parts of docks, twisted pieces of metal and lots of brightly-colored fishing floats. By the end of the day, we’d pushed, pulled and wrestled a pretty decent pile of debris back to camp – a pile big enough to make us feel that we’d earned a game of bocce buoy and a few mugfuls of box wine.

The Flores shoreline. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

Junk from the other side of the ocean. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

The nefarious single-use water bottle. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

Chico Amato on a long walk back to camp. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

A day’s work filled 18 industrial garbage bags. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

The little-known sport of bocce buoy. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

The next morning, after we’d sorted the haul and dragged it all down to the waterline, the Coast Guard boat rounded the point and started ferrying loads back to Tofino. On the trip back to town, weaving through the constellations of rocky islets that form the outer reaches of the Sound, I was struck again by how hugely beautiful this coast is and how worthwhile it is to put in the work to protect it. We’re lucky to have escaped the worst excesses of industrial civilization here, but we can’t just sit back and hope it stays that way. It takes a lot less work to break something than to make it whole again, especially when that thing is a living ecosystem with intricacies that we still don’t fully understand.

By late afternoon, the Coast Guard had helped us get almost 900 pounds of garbage from the beaches of Flores to the docks of Tofino, where we heaved it all into a pickup bound for the recycling depot in Victoria. I walked home that day hoping that, instead of leaving no trace at the beach, we’d actually left it a little better. Being out in wild places and seeing the impact we’re having on the planet can be pretty discouraging, but I’ve been learning that the only way to work against discouragement is to start making small motions to tend to the place you live. Nobody else is going to do it, so you have to get out there and do it yourself. Whether you’re a surfer, a climber, an angler or a Sunday stroller, the more time you spend in the field the more you see that the land that has cared for your heart and your soul could really use some care in return.

Chico and Weeze ferrying trash to the Zodiac. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

Much credit to the Coast Guard for their patience and pilotage. Photo: Malcolm Johnson

The crew and their 900 pounds of treasure. Photo: Malcolm Johnson