Born with This

The last days of the Klamath River dams.

The Hornbrook Chevron looks like any other place to buy gas, snacks and a fishing license along the I-5 corridor in Northern California. It’s also one of the few businesses still standing in Hornbrook, California (population around 200). For a few hours though, it comes to life because the Chevron parking lot is the unofficial rendezvous point for fly-fishing trips on the upper Klamath River. It’s here that guides meet anglers, coffee chases donuts and steelhead strategies hatch.

It’s here, on a near-perfect fall morning, I meet up with Patagonia ambassador and California Trout (CalTrout) videographer Mikey Wier and his colleague Andrew Braugh. For 50 years, CalTrout has been at the vanguard of wild fish conservation and the fight to preserve California’s waters. Wier has chased trout and salmon across the world and has the 1,000-yard-stare and unflappable air to prove it. Braugh, CalTrout’s Mt. Shasta/Klamath regional director, offers an eager, earnest welcome to Siskiyou County. As we lean against Barugh’s drift boat and make fish talk, a trucker ambles over. He’s seen the drifter and wants to talk fishing, too. Everyone here does. I ask him what he thinks of the Iron Gate Dam, just 9 miles up the road. Is it time it finally came down? “I just don’t know,” he says. “I really don’t. But I do want to see these fish do well.”

Dam controversy or not, this will always be true; nobody hates salmon.

Our small crew has come to Northern California to explore the Klamath, a once generous river now cut in half and nearly broken. Can a river that once hosted the third most abundant salmon runs on the West Coast overcome a calamitous history of dams, mining, logging and numberless other insults? Can it be a welcoming home again—not just for fish—but for the people who live, work and pray on its banks?

We’ve also come to chase a rumor that the days of the four most-downriver Klamath dams may be numbered. There are whispers that stakeholders are inching closer to an agreement to restart the most significant dam removal and restoration project in US history. We’ve swallowed the heartbreak of dashed deals before. A 2016 agreement to remove these dams crumbled in July 2020 primarily due to liability concerns voiced by their operator, PacifiCorp. It was a bitter pill just weeks before salmon were to begin their spawning push.

Full disclosure—I’m also here to do a little fishing. The hope is to get lucky and connect with a wild Klamath steelhead. Touching a whirling mass of will, beauty and perfection for a breathtaking moment—and then letting it swim away—is a humbling way to taste the elemental power of a river.

We’ll follow California State Route 96, which stalks the Klamath along its route to the ocean—from the upriver farmers and ranchers to the river’s mouth, the ancestral home of the Yurok Tribe.

“In the rural West, there is a real fear that environmentalists are out there to take the water or sue you and put you out of business. Perceived or real is beside the point. We have to counter that and offer solutions.”

The chilly morning ripens into a delicious day, and we drive to just below the Iron Gate Dam, where we’ll launch the boat. Along the way, we pass homes (cozy), campgrounds (half-full) and restaurants (closed). We also pass the first of what will prove a constant: a green State of Jefferson flag.

Decades-old, the State of Jefferson secessionist movement found momentum during the Trump years. Anti-tax, anti-regulation, pro-gun and staunchly libertarian, the Jefferson Staters want to establish a 51st state in conservative stronghold counties of Northern California and Southern Oregon. When it comes to removing the Klamath River dams, they’re an ornery “no.” More than any other group, the truculent Jefferson Staters symbolize just how stark the division over dam removal can be.

“Up here, it’s like dam removal is the end of civilization,” a spokesman for the dam’s owners, PacifiCorp, told a reporter. “Downriver, the dams are the root of all evil.”

The fact is, the Klamath dams are inefficient and an ever-increasing burden on the region. According to a 2008 study by the Public Utilities Commissions in Oregon and California, the dam’s electricity customers would save more than $100 million by bringing the Klamath River dams down, rather than spending more than $500 million to service them. These are the sort of estimates that never seem to decrease, and the liability is undoubtedly much more significant now. However, PacifiCorp customers have already paid for the dam removal. In January 2021, PacifiCorp announced that they’d collected $200 million in surcharges from their Oregon and California customers. The remaining $250 million needed for removal and restoration will come via a State-of-California bond.

Money aside, if there’s any hope for the Klamath’s imperiled salmon and steelhead, the dams need to come down.

A river cut in half. With no fish passage, the Iron Gate Dam is the end of the road for Klamath River salmon and steelhead. Photo: Jeremiah Watt

The Klamath is a particularly beautiful river. From its start in Oregon to its broad mouth emptying into the Pacific, it describes a way of life for those lucky enough to live near it. It is used for irrigation, electricity and recreation. It is also the home to salmon, steelhead, bull trout, rainbow trout, coastal cutthroat trout and Pacific lamprey. But these are more than just fish; they’re the physical and spiritual lifeblood of the Yurok and other tribes who have lived on its banks since before time was counted on calendars.

Yurok is a word that comes to us from their neighboring tribe, the Karuk. It means “downriver.” At around 5,000 enrolled members, they are the largest Indigenous tribe in California.

“Iron Gate” is an English phrase meaning “property of PacifiCorp.” PacifiCorp is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway Energy, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, a multinational conglomerate holding company controlled by a man named Warren Buffett. As of April 2021, Buffet was the sixth wealthiest individual on the planet, worth $98 billion.

Completed in 1962, Iron Gate is the lowest dam on the Klamath. It is an earthen embankment, standing 172 feet tall with a length of 740 feet. Its two turbines can generate 18 megawatts of electricity, roughly enough to power around 14,634 homes for a year. However, due to silt buildup, it’s estimated that the dam is now operating at half capacity. In comparison, a typical 2.5-megawatt wind turbine can provide electricity for about 2,000 homes. Replacing the power produced from these dams is no longer an issue.

Iron Gate stands at the midpoint of the Klamath. In reality, however, it is the end of the road. The dam was built without any way for salmon and steelhead to get over or around it, slamming the door on fish attempting to reach spawning habitat upriver. As an attempt at mitigation, there is the Iron Gate Fish Hatchery, a glum structure ornamented only by a deserted picnic area.

According to the California Hatchery Review Project, the hatchery goal has been to release about 6 million fall Chinook—also known as king salmon—annually. Additionally, 200,000 steelhead smolts and 75,000 coho smolts are scheduled to go into the river each year, though these numbers often vary dramatically. Despite this effort, Klamath steelhead and salmon populations continue to plummet.

I wander around the facility, trying to get a sense of the place. From any perspective, Iron Gate is not beautiful. It looks like all dams—gurgling black froth, attended to by seagulls, decorated with pipes, pumps and heavy machinery. The smell of ozone and diesel tinges the air. When you get close, the brutalist structure hums, a barely perceptible drone that never ends.

There is an actual iron gate guarding the pumphouse. A placard lets me know I’m not welcome. I make my way down to the river, where I run across two anglers visiting from Colorado. They’ve hired a local outfitter to guide them for the day. The forecast? Fair. Only a few battered Chinook ghost through the pools. As for steelhead? A firm maybe. There are reports of scattered sightings. But trout? There are always trout.

The anglers take a few selfies by the sun-speckled drifter, joke, scrutinize fly boxes—regular boat launch stuff. Before I can bring up the subject, one of the anglers jerks his thumb over his shoulder. “Hopefully, when we come back in a year or two, that dam will be gone. This may be the last time we have to look at it.”

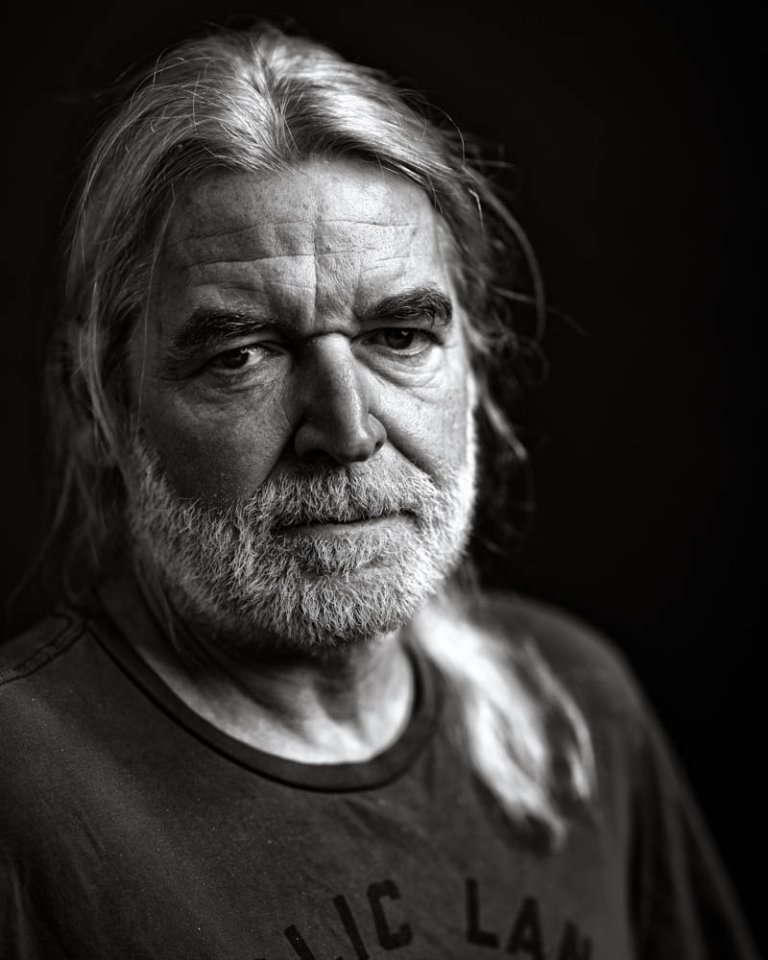

Before heading downstream in search of a wild steelhead, CalTrout’s Mikey Wier takes an unsentimental view of PacifiCorp’s Iron Gate Dam on the Klamath River. Photo: Jeremiah Watt

Finally, we hit the water. It doesn’t take long before we find a trout, then another and another. The early success is a pressure-release valve, freeing us to think about things other than fishing. Braugh is eager to talk about his work on the river.

Dam removal is more than just dynamite and excavators. There’s habitat to restore and concerns about flooding, sediment and property values. But what most concerns people on the upper Klamath is irrigation. How will we keep the crops watered and the cows happy?

Braugh’s job is to build relationships with the basin’s ranchers and farmers—the stakeholders most interested in a reliable water flow. The goal is to implement water-management strategies to control irrigation more efficiently while restoring habitat in the tributaries that cross the ranch and farmland.

“In the rural West,” Braugh explains, “there is a real fear that environmentalists are out there to take the water or sue you and put you out of business. Perceived or real is beside the point. We have to counter that and offer solutions.”

For Braugh, that means something he calls “kitchen table” talk. “We have to demonstrate that we understand their point of view,” he says. “If you can’t establish a rapport, you’re not going to get through the front gate, let alone get to the kitchen table to talk about real, constructive solutions.”

It’s crucial that CalTrout confront the fears and misinformation ranchers and farmers face. “The important thing to remember,” he says, “is that they see themselves as stewards of the land, too. But they also don’t want to pass down a ranch that’s under litigation or facing the threat of being shut down. If you can reduce that fear, it changes how they think about their entire future. Nobody hates salmon.”

When not fretting about potential litigation, Braugh notes that ranchers are deeply concerned about utility costs. For CalTrout, that’s a conversation starter. By modernizing operations, ranchers and farmers save money. “If there’s meaningful value for them, they’ll listen.”

The kitchen-table talk is working. “We know how to grow cows, but we don’t know how to grow fish,” says Blair Hart, a fifth-generation cattle rancher, “but we’re gonna learn.” With the help of CalTrout, Hart Ranch is becoming a model of efficient water management, reconnecting and opening up more than 10 miles of habitat on the Little Shasta River. On Cardoza Ranch, a similar project has opened 14 miles of habitat on the Parks Creek tributary. “To keep this ranch intact—which has been in our family for 169 years—the only way to meet regulatory demands coming from society is to become efficient,” Hart says.

Although California State Route 96 is a breathtaking drive through Northern California’s most remote parts, the area is struggling. Throughout the watershed, people have been battered by a triple whammy of catastrophes. Yearly fires have devastated homes, businesses and communities. COVID-19 has ravaged the area, killing indiscriminately. Finally, the economic realities in the area are harsh. Unemployment, bankruptcies, homelessness and drug addiction have been ruthless here. The reality of the situation is hard to fathom with the galloping river ornamenting a redwood forest set against a crisp autumn day. Yet along 96, the anger, mourning and confusion are palpable.

Happy Camp, California, 77 twisty miles east of the Iron Gate Dam, is the headquarters of the Karuk Tribe. According to a crumbling chamber of commerce sign, it’s also the “Steelhead Capital of the World”—an unsanctioned title disputed by many.

When we pull into town, the surrounding peaks are still charred from last summer’s horrific burns. On September 8, 2020, the Slater and Devil Fires rushed toward the town’s main street. By the time the flames were doused, nearly 160,000 acres were torched, 158 homes had burned to the ground, a dozen people were injured and two firefighters had lost their lives. The fire left half the town homeless. Red Cross vehicles sit idle in the street, their drivers still working out how to help people. For a village with a population of around 850, it’s a lingering nightmare.

“We couldn’t see across main street because of the smoke,” Daniel Effman, owner of Partners Deli and Arcade, tells us. “People were hiding along the riverbank to escape the fires coming down.”

Tragic as they are, these situations have a way of bringing people together, especially in tight-knit communities like Happy Camp. As soon as the smoke cleared, Effman began providing free food to the community. “Your money’s no good in Happy Camp,” he told neighbors.

Overlooking the Salmon River just before its confluence with the Klamath. Photo: Jeremiah Watt

On its route to the sea, hundreds of streams and creeks feed the Klamath. One of its main tributaries is the 19-mile long Salmon River. It is unspoiled and undammed, and as we get closer, Wier’s steelhead senses start tingling. We turn off 96 and head upriver to explore a particular spot he knows to be “epic.”

Toss a rock over the bridge crossing the Salmon River and it plummets in a woozy arc. It collides with the river in a splat that echoes off the sheer rock walls guarding a majestic pool just below a waterfall. If there are fish anywhere in this system, it should be here—we should see them from the bridge. We don’t see anything. But, when it comes to steelhead, Mikey Wier is a gamer.

He negotiates a barely-there goat trail, hug-slides the canyon wall’s warm rock and boulder hops until he’s descended 500 feet to the pool. This is Karuk tribal land, and on the bridge, there can be no mistake. The structure is tagged “Indian Pride,” and the hashtag #landback stands out in black spray paint. Next to “This Is Native Land,” someone has carefully rendered the Karuk word OOK (meaning “here”) with arrows pointing up, down, left and right.

It doesn’t take Wier long to connect with a fish, but it’s a small trout, not the steelhead we’re targeting. While he casts, it’s impossible to ignore just how loud the quiet here is. From below, the river whooshes, while above, the breeze hums and hisses through the green canopy.

Just a few miles downstream is Katimin, an ancient village site and a place the Karuk speak of as the “center of the universe.” Gold miners burned the village to the ground in 1852, and colonizers torched it again in 1883. By the 1950s, the government owned the land. It sold four acres to a man who constructed a riverside fishing lodge, a few cabins—and a fence—forcing the Karuk to perform traditional renewal and salmon-welcoming ceremonies off the property.

During the offseason, the lodge’s owner raised marijuana seedlings later transplanted to a grow operation deep in the Klamath National Forest. Busted in 1993, he was facing serious drug and weapons charges. Striking a deal, he forfeited the land and bartered down to a state weapons charge. The feds put it up for sale, but there were no takers. Finally, after a year of negotiations, the government returned the land to the Karuk. Not a progressive land-return policy, but something, I guess.

“We see these dams as a monument to colonialism. This was about destroying people and culture for profit. We have ceremonies that require people to pray in the river. You can’t pray if you can’t even go into the river because it’s toxic. We want to fix things. We want to restore habitat, and we want to eat more healthy salmon. Costco chicken ain’t cutting it. But it’s not just for the tribes. It will benefit everyone.”

Eighty miles downstream and just 4 miles from where the Klamath River empties into the Pacific Ocean, the town of Klamath, California, doesn’t have that battered look or the scattered State of Jefferson flags from upriver. Instead, it looks as if someone simply turned off the lights, a reminder that COVID-19 is very real here. The still-new Redwood Hotel Casino is dark. Most restaurants are shuttered. Work is getting done, however. This is Yurok headquarters.

Before colonialism, the Yurok spread upriver and along the coast, populating more than 70 known villages. Change—monstrous change—was coming. Spanish colonizers anchored off Trinidad Head in June of 1775. The invaders climbed the peak, planted a cross and claimed dominion over the land, warning the Yurok to accept Christianity or face the consequences.

By the time the Spanish made it to Northern California, waves of colonialists had been stealing, slaving, raping and murdering in North America for almost 300 years. Soon, what was to become Northern California was being raided by the Americans, Spanish, English and Russians—all hungry for plunder. Land, pelts, fish, fresh water and timber were all on the menu. They took what they wanted. There were no rules. There were no limits.

Reeling from the first wave of the invasion, the California Gold Rush, which began in earnest in 1848, flung the Yurok into deeper chaos. Rather than a romantic American interlude, the Gold Rush was one of world history’s most devastating ecological events. With the miners came pollution, exploitation, land theft, and cultural and physical genocide. A grim passage in the preamble of the Yurok Constitution illustrates the oppression: “Our social and ecological balance, thousands and thousands of years old, was shattered by the invasion of the non-Indians. We lost three-fourths or more of our people through unprovoked massacres by vigilantes and the intrusion of fatal European diseases. The introduction of alcohol weakened our social structure, as did the forced removal of our children to government boarding schools … After gold miners swarmed over our land, we agreed to sign a “Treaty of Peace and Friendship” with representatives of the President of the United States in 1851, but the United States Senate failed to ratify the treaty. Then in 1855, the United States ordered us to be confined on the Klamath River Reserve, created by an executive Order … within our own territory.”

Not content with constraining the Yurok to a sliver of their ancestral lands, Congress passed the Dawes Act of 1877. Arguing the reservation had been abandoned, the Act gave small parcels of land to individual Yuroks. It offered the “surplus” to homesteaders. It was land theft on a massive scale, opening the door to widespread logging, mining, habitat destruction and declining wildlife populations. It was also the first sign that something elemental to the Yurok way of life—the salmon—could be taken from them.

In yet another devastating blow, the State of California declared traditional fishing by Yurok people illegal. It took another 50 years and almost constant legal, and even physical, battles for those rights to be reaffirmed.

Before completion of the dams on the Klamath River, it boasted the third-largest salmon and steelhead runs on the West Coast. Despite the fact that runs have fallen to below 10 percent of their historic numbers, fly anglers have yet to run out of hope. Photo: Jeremiah Watt

“When they put the dams in, it cut the river in half,” says Barry McCovey Jr., a Yurok tribal member and their senior fisheries biologist. McCovey Jr. speaks in long paragraphs about complicated things like genetics, salmon returns and escapement. It can be challenging to keep up, especially when seals are chasing salmon in the bay behind him. “Basically, the dams destroyed the ecosystem,” he says. “We see these dams as a monument to colonialism. This was about destroying people and culture for profit. We have ceremonies that require people to pray in the river. You can’t pray if you can’t even go into the river because it’s toxic.” He’s referencing the algae blooms that accumulate behind Iron Gate. In the summer, this algae is released into the Klamath, coating the river bottom and banks with green slime. “We want to fix things,” he continues. “We want to restore habitat, and we want to eat more healthy salmon. Costco chicken ain’t cutting it. But it’s not just for the tribes. It will benefit everyone.”

I ask him about the dam’s defenders. How do you convince someone flying a State of Jefferson flag that dam removal could ever be a good idea? “It’s just misinformation,” he says. “Everything that we have in this watershed evolved in this flow regime. If you feel like dam removal will hurt fishing opportunities, speak to a scientist. Don’t rely on Facebook. Look at the research. Look at science.”

The question that everyone wants scientists like McCovey Jr. to address is, what happens next? We’ve seen the effects of dam removal on Washington’s Elwha River, where fish were blocked from upstream migration for close to 100 years. Following the breaching, summer-run steelhead came roaring back and are now thought to be the most robust of any river on the Washington coast.

McCovey Jr. describes how his team closely tracks the science surrounding dam removal, including attending academic conferences and establishing close ties with the scientists studying the Elwha. “Rivers are resilient. Fish are resilient,” he says. “Our fish runs are depressed. There’s no doubting that. As a scientist, I’m seeing increased disease exacerbated by dams and climate change. The dams warm up the river, and we see the toxic algae, which is quite literally killing fish—the dams are killing fish. There’s no doubting that it could start to turn around, but we need to be patient. It took a very long time to fuck this up, but things will get better.”

Then the obvious question. “What about the rumors?” I ask. What happens when the dams do come down? Will it be a celebration? Will it be bittersweet? He looks across the estuary. A few hundred yards away, the Klamath is becoming the Pacific. The sound of gulls and pounding surf mixes with the wind. “It’s been a long time,” he says. “People have dedicated their careers, their lives. People have died in the attempt to remove those dams. It’s certainly going to be a victory. I can see it being very emotional. As Yurok, restoring balance and fish is something we’re born with. I was born to do this, but we also understand we’ll always be fighting for this river. When I see those excavators, I’ll let you know.”

“We were promised so much with those dams, and when they came in, it was the end of everything. We battled for this river, and we won that battle. For thousands of years, we have never been defeated here.”

Yurok tribal member and fishing guide Pergish Carlson surveys his tribal land, his backyard and his home waters—all at the same time. Klamath River, California. Photo: Jeremiah Watt

Yurok tribal member and fishing guide Pergish Carlson is quiet. Not standoffish quiet, but warm quiet. The sort of quiet that, when he begins a story, you lean in. “Our creation story begins here,” he says, sliding his river sled into the water. We are launching just a few miles from the Pacific Ocean. The Klamath is languid and easygoing here, far different from the bustling waters below Iron Gate. “This is where my people come from. This is where my ancestors are buried.” He points to a hillside across the river from a clear-cut only a few seasons old. “My grandfather is buried just up there.”

The Yurok have lived on this river for generation upon generation. The redwoods that line the bank have seen centuries of the river. Carlson himself has plied these waters for more than four decades. The steelhead we fish for have been here, in a practical sense, forever. The trees, the people, the fish and the river all describe history in humbling magnitude. It is time with a capital T.

It’s a privilege for someone like me to fish Yurok land. The abundance. The fragility. The palpable sense of spirit. It is also disorienting. That sense of time is heavy, like something we have put on—a formal frock of reverence.

As upriver, big wild steelhead are just not around. Instead, we amuse ourselves with “half-pounders”—juvenile steelhead that return to the river after less than a year at sea. They are feisty and eagerly pounce on our flies. It’s easy, fun fishing.

While the rest of the crew engage the half-pounders, I walk with Carlson down a broad gravel bar. At every bend, every riffle, there’s a connection. He points out an old tribal village location and then, across the river, another. “Anywhere a creek comes in,” he says, “there was a village. Ten or 12 structures and families per village. They were made of wood,” he chuckles. “We left no carbon footprint.”

I look up into the trees and try to imagine life on this river. Carlson obliges my imagination, telling me about the many ways the Yurok would harvest salmon. “We’d gather white stones and place them on the bottom of the river. When they swam over the stones, we’d spear them.”

As we walk, he explains the Yurok pioneered adaptations that allowed them to live in an intimate embrace with the earth. They not only conducted controlled burnings to suppress wildfires, “so we could walk around the forest,” but also used those burnings to safeguard the salmon. “When the river got hot, we would do burns. The smoke would create an inversion layer that would cool the river by three or four degrees, allowing the fish to come up.”

I ask how it feels to float this river and walk these gravel bars in the shadow of so much history so close to the bone. “In the quiet times when I’m guiding, I’ll think about that,” he says. “It’s something not many people can have—can understand. I feel lucky. I feel it’s a real privilege.”

I ask Carlson if the rumors are true. If the dams are coming down. It’s a serious question, but he grins like he’s in on a secret which, it turns out, he is.

“We were promised so much with those dams, and when they came in, it was the end of everything. We battled for this river, and we won that battle. For thousands of years, we have never been defeated here.” He pauses, nodding at a memory. “I had them all on my boat,” he says, “all the big guys from PacifiCorp. I had fished them all day, and at the end, one of them said to me, ‘I can’t wait to come and fish with you again.’ I told him, ‘No. You can’t fish with me until those dams start coming down. When that happens, then I’ll take you fishing.’ That was the last thing I said to him.”

Holding a traditional basket, Yurok General Counsel Amy Bowers-Cordalis announces that a Memorandum of Understanding has been reached to bring down four dams on the Klamath River, reconnecting the watershed and opening more than 400 miles of salmon and steelhead habitat. Photo: Jeremiah Watt

In many ways, Amy Bowers-Cordalis is the public face of the Yurok. As the tribe’s general counsel, she appears before cameras, journalists and judges. She has fought the complex, slowly grinding negotiations and mediations that have taken place behind the scenes of the dam struggle. She is self-assured, with a mind two questions ahead and a surprising, boisterous laugh.

I meet her in a small park overlooking Houda Point Beach and the magnificent stack rock formations standing sentinel in the Pacific. We are only a short distance from Trinidad Head, where the wheels were set in motion for genocide. “This is still Yurok country,” she tells me. “It was good living here.”

There is a video camera. Bowers-Cordalis answers questions patiently, outlining the river’s history, the dam’s legacy and the tribe’s position. She speaks at length about climate and racial justice on the Klamath, about how important reconnecting the river is to the Yurok. Finally, the camera gets put away, and I ask her if she’s about to make history. If the worst kept secret in Northern California is true. She unleashes her robust laugh and almost shouts, “Yes! The dams are coming down!”

A few moments later, I’m on the phone, tapping at my laptop in the parking lot. I have one more thing to do. One more keystroke to punctuate what the Klamath wants us to know. I hit send.

PRESS RELEASE

“Those dams are coming down!” exclaimed Amy Bowers-Cordalis, general counsel for the Yurok Tribe. Speaking to Patagonia Fly Fish, she broke the news that a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) had been reached to bring down four dams on the Klamath River, reconnecting the watershed and opening more than 400 miles of salmon and steelhead habitat. The memorandum signifies an agreement between the states of Oregon and California, the Yurok and Karuk Tribes, the dam’s owners PacifiCorp the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission as well as the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, a nonprofit responsible for dam removal and related restoration. “The MOU is the right step—the first step,” Bowers-Cordalis said. “We’re in this for the long haul, and to be back on track and to feel like we have this understanding is everything. Now, we can look ahead to taking steps to finally heal this river.”