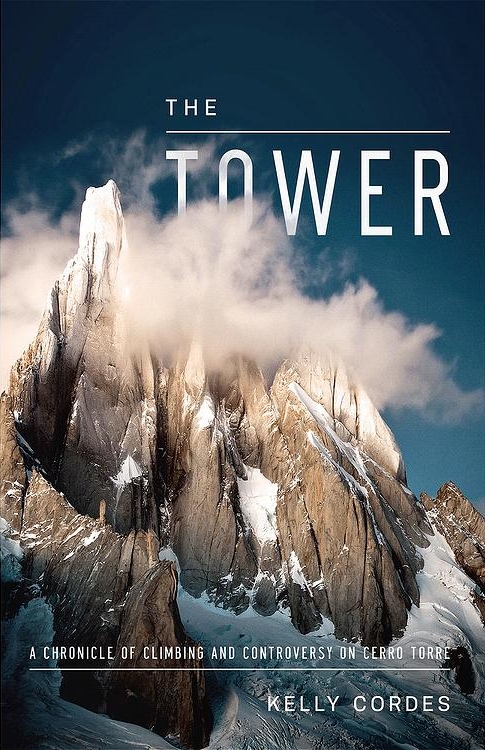

Excerpt from “The Tower: A Chronicle of Climbing and Controversy on Cerro Torre” by Kelly Cordes

At the wind-scoured southern tip of Argentina, between the vast ice cap and the rolling estepas of Patagonia, rises a 10,262-foot tower of ice and rock named Cerro Torre. Considered by many the most beautiful and compelling mountain in the world, it draws the finest and most devoted technical alpinists from around the globe. Reinhold Messner, the greatest mountaineer in history, called it “a shriek turned to stone.”

I began work on my book in spring 2012, after the Compressor Route de-bolting controversy. On a broad level, I’d gained a glimpse into Cerro Torre’s complex and layered history during my dozen years as an editor for the American Alpine Journal. On a personal level, I’d grown familiar with the spectacular mountain in January 2007, during my climb with Colin Haley. But once I began my book research, I became intrigued by how the intertwined stories of Cerro Torre—this wholly uncaring, inanimate object—seemed to reflect the best and worst of human ambition, and how often our actions are fueled by the power of belief. My notes and threads related to the main stories could fill several volumes.

By the time I finished, I’d conducted in-person interviews in seven different countries, researched original documents dating back to the 1950s, and worked harder than I have at anything in my life. The final manuscript is 77,000 words, which is on the short end for non-fiction books. My first draft was almost double that, but ultimately I think the book works better at this tighter length. Most of the chapters are short, which I like for pacing. The final page count, however, is 400, due to the appendices, my 256-entry selected bibliography, and the 150 photos, including archival shots never before published. The book opens with a sixteen-page color gallery of the mountain from different angles and in different moods, and the middle has another 16-page color gallery.

In terms of genre or category, I’d call the book narrative nonfiction. I blend reporting and in-depth research with first-person storytelling as I try to unravel and understand some of Cerro Torre’s mysteries.

A view from the southern end of the Torre Valley, showing the prominent Cerro Torre and Torre group. Photo: Mikey Schaefer

A view from the southern end of the Torre Valley, showing the prominent Cerro Torre and Torre group. Photo: Mikey Schaefer

From Chapter 9 – Body of Evidence

Jim Donini, John Bragg, and Jay Wilson had made a groundbreaking ascent. While multiple routes might ascend a mountain over the decades, there is only one first ascent. Along the way, they had been the first party to repeat the famed Egger-Maestri line to the Col of Conquest.

What they found, and what they didn’t, was the most significant evidence concerning the ascent claimed by Cesare Maestri and faithfully backed by Cesarino Fava.

Things got perplexing only a thousand feet up—just halfway to the Col of Conquest.

“Immediately [upon starting up] we started seeing artifacts. It was like, ‘Oh, my god,’ because we were young climbers and in those days most climbers read all about the history. I had read books by Gervasutti, Bonatti, Hermann Buhl, Lionel Terray, and all the Europeans, and they were supermen, and we were climbing through history and we found a piece of rope hanging, and a wooden wedge, and some old bolts, and some pitons,” Donini told me.

In the lower dihedral—the first thousand feet to the equipment dump, just below the triangular snowfield—artifacts were everywhere. Fifty, a hundred pieces of gear, they lost count.

On the last pitch to the equipment dump, the final section of the old fixed rope was peculiar. For the entire pitch the gear was spaced surprisingly close together, every two feet or so. And the rope was clove-hitched to approximately every other piece. Nobody could explain it then or now; it serves no conceivable purpose. This was the only pitch fixed in such a manner.

Alongside that final section of the 1959 fixed rope, sixty feet below the equipment dump, a pronounced block of rock protrudes from the wall. A pair of thin, nylon climbing ropes was anchored to the wall a short distance below the protrusion. The double ropes then ran up and over the block, and then down the other side. About twenty feet down, their ends were broken and frayed. Just like the rope ends found with Egger’s remains. The ropes appeared to be identical. “I wasn’t sure,” Donini told me. “I’m still not sure—but they were just hanging there.”

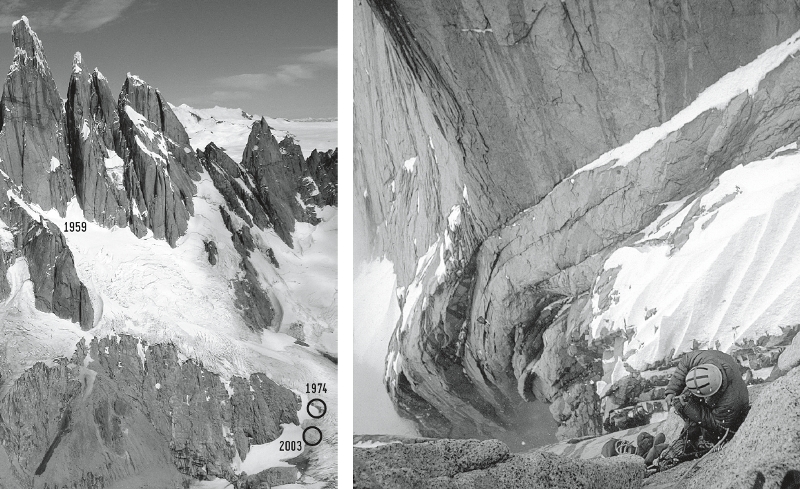

(left) The upper Torre Glacier, showing where, according to Maestri’s account, Toni Egger presumably died after being swept from the wall in 1959, and the locations of Egger’s remains found in 1974 and 2003. In early 2014, slightly up-glacier from the 2003 site, Rolando Garibotti found several pieces of Egger’s sweater melting out of the ice. Photo: Rolando Garibotti

(right) Looking down on the hidden traverse ramp leading to the Col of Conquest, as seen during the first ascent of Torre Egger. The Col of Conquest is off-photo just to the right, while the triangular snowfield is visible below and left. Photo: Jim Donini

ABOVE, EVERYTHING FLIPPED like a switch.

“We had read the accounts where Maestri said the first part was difficult, vertical. Then he said the part from there to the corner, before you made the traverse into the col, was easy, lower angle. Then he said the traverse was very difficult. Now, this is exactly how it looks as you’re looking at it from below.”

Then two things happened: “One, from that equipment dump to the Col of Conquest—and we went back up and down it a few times—we found zero artifacts. Now, that is not completely damning, although it’s pretty damning. You know how it is, you’re on a route and there are natural lines, and also rappel lines, and you always run into stuff if people have been there—especially after we’ve seen fifty to a hundred pieces below. But none, zero, and not even any rappel points. And we’re really looking around, looking for rappel pieces, and just nothing. I’m going, well, this doesn’t make any sense.”

As they climbed farther above the last traces of the purported 1959 climb, their doubts mounted. “The other thing was that the route description turned out to be different from the way it looked. The climbing from the equipment dump to the traverse was harder than it looked—it was lower angle overall, but you’d get a little headwall here and there—it was real climbing. But all of a sudden you get to the corner, and you turn around the corner and there’s a ledge.”

This is the section that looked so daunting from below, where Maestri reported the most difficult climbing of the route. “You couldn’t see it from below because of the angle. The only place you can see that ledge from as you’re going up is when you get right on it and you turn the corner and it’s ten feet from you. There’s a couple of fifth-class moves to get to it, and then it was fourth class—scrambling—to the col. It was by far the easiest terrain on the entire climb.”

The terrain above the last traces ever found of the 1959 team was the opposite of how it looks from below, completely different from what Maestri described. The Americans hadn’t even finished their climb by the time the evidence was undeniable. “I knew right then and there that Maestri had not only not climbed Cerro Torre in 1959, but he didn’t get to the Col of Conquest. I think his high point was the goddamned equipment dump,” Donini said, still incredulous. “Only a thousand feet up.”

The Tower: A Chronicle of Climbing and Controversy on Cerro Torre is now available from Patagonia.com and other fine booksellers. One percent of the sales from this book go to the preservation and restoration of the natural environment.

“Kelly Cordes embodies the climbing spirit more than anyone I know. I admire him for the way he devotes himself completely to writing and the mountains. He is also my favorite storyteller. I can think of no one better to write the story of Cerro Torre.”

–Tommy Caldwell, professional climber

“There’s no one in contemporary alpinism better than Kelly Cordes at combining cutting-edge climbing talent, a wicked sharp pen (OK, keyboard), and a passion for accuracy in mountain reporting.”

–John Harlin III, author of The Eiger Obsession

No mountain in the world is so otherworldly and has such a troubled history. This book is the most in-depth look yet. It examines the sociological and psychological contexts that have sparked fifty years of controversies and rivalries, and how belief influences everything we—both climbers and all of mankind—do.”

–Rolando Garibotti, author of Patagonia Vertical

“With passion, literary skill, and relentless curiosity, top-shelf alpinist Kelly Cordes takes us on a wild ride through the controversial history of Patagonia’s Cerro Torre—the most perfect mountain on earth.”

–Gregory Crouch, author of Enduring Patagonia

Update 1/5/14: Listen to Kelly talk about his book on NPR’s Here & Now.