A Matter of Breathing

Running won’t solve the issue of wood pellet biomass pollution. But it can ignite community and conversation—and that’s a start.

Listen to the story

All photos by Elroy Johnson

It’s 7:30 a.m. on the entrance road of Mississippi’s Homochitto National Forest, just over 30 miles from the nearby town of Gloster. Morning light has begun to hit the towering pines, oaks and hickories when the first bus of runners arrives. Pale sunbeams streak through the trees, turning the forest’s canopy a rich, golden green. Shadows play across the dirt singletrack that winds through these woods, mimicking the excitement in the air as the runners step down from the bus and filter into the Clear Springs Recreation Area. For now, the trails are quiet, but soon they will be filled with cheerful footsteps. Everyone is here to move in two of the simplest ways possible, running and walking.

In another sense, however, the crowd’s reason for being here is anything but simple.

Forests throughout the Southeast are increasingly a source of harm for those who live among them, thanks to wood pellet biomass—a fast-growing alternative energy export in the US. Trees and wood waste are pelletized and shipped overseas to European power plants that burn them to supply their grid. The industry is touted as a viable green energy substitute for coal, but the truth is complicated. Environmental groups have documented truckloads of whole trees on their way to biomass companies, despite industry claims that pellets are largely sourced from wood waste. Cutting down forests leads to habitat fragmentation, biodiversity loss and increased erosion and flooding.

What’s more, processing plants spit out air pollutants that research shows can cause a suite of respiratory and other health issues to those nearby. In 2021, the state of Mississippi fined a UK-headquartered company called Drax Biomass $2.5 million for emitting three times more air pollution than legally allowed. In Louisiana, Drax agreed to pay $3.2 million in state penalties over similar air pollution.

Pellet production often occurs in low income or Black communities where residents tend to be politically and socially disenfranchised—a common reality for heavy industry presence.

A crisp September morning made for perfect running and walking conditions as the 2-mile runners made their way around the Clear Springs Recreation Area campground.

Gloster, Mississippi, is one such place. This town of roughly 1,100 is about 72 percent Black, with 38.5 percent of the population living below the poverty line, and has limited access to medical resources. (The median household income in Gloster is $18,814.) A UK biomass company called Amite BioEnergy, which is owned by Drax, operates a 2,548-square-mile wood-sourcing operation stretching across Southwest Mississippi and into northern Louisiana. This company also owns a processing plant about a mile from town.

Many residents speak of respiratory illness, cancer and unexpected deaths in the community, and little advocacy on their behalf. But they also rely on the biomass operation to pay for the town’s utilities.

“It’s good to have the plants here in Gloster, but we want them to protect us,” says Gloster resident Mabel Williams. “I’ve been seeing problems with people’s breathing and a lot of people have been sick. I heard that one lady who lived near the plant lost two babies. That affects the community.” Drax has twice violated air-quality standards and faced fines, but in those situations, funds often don’t reach the communities that are directly impacted by the pollution.

Gloster resident Mabel Williams shows off her NAACP card. She was a part of the local NAACP charter in 1959.

I first found out about the harms of the biomass industry as a grad student in North Carolina. After seeing large swaths of cut forest firsthand, I learned about the biomass industry and decided to follow the examples of other runners who’d used their sport for activism. I wanted to create an event that would build community and encourage civic engagement against harmful biomass production. I began engaging on the issue through Dogwood Alliance and Southern Echo, which ultimately led me to Gloster. Together, the Gloster community and I created the Equitable Action Run Towards Health (EARTH): a forum for communal movement near the source of the very same extraction that is affecting those who live close by.

The EARTH run was a family affair, as kids and adults of all ages came together to walk, run and enjoy time outside.

We chose to host the event at the Clear Springs Recreation Area. This campground is a portal to miles of public forest, but many of those who joined us said they had never visited its lake, walking paths and trails. In the Southeast, most land is privately owned, which makes recreation more difficult and biomass business a bit easier—because companies own the forests they’re cutting or lease them from the people who do. In Florida, North Carolina, Arkansas and Tennessee, more than 174,000 acres of public land are surrounded by private property, with no public roads or trails to access it. Access issues have been exacerbated by a long, complex cultural tradition of excluding Black and brown people from the outdoors.

Many in Gloster speak about limited access to trails and recreation, and about not wanting to be in unfamiliar places without a trusted friend. Many share negative perceptions of the outdoors and have experienced fearmongering about where Black people are expected to be. In places like Gloster, you don’t hear people talking about going on adventures or taking sport-related risks because here, the outdoors come with a very different set of risks: that of violence from other people.

As a kid growing up in Georgia, I was headstrong and perhaps naïve in my resolve to experience the world as I wanted to, despite others’ warnings. My formative experiences as a runner were in places like this national forest. The backwoods of Georgia, North Carolina, Texas and Mississippi have greeted my feet and fueled my breath, curiosity and love for the environment. Though in the back of my mind, there has always been always a familiar concern.

Am I allowed to be here?

Am I safe?

Simply existing here comes with a threat of violence that’s rooted in the history of my ancestors’ enslavement.

For all of these reasons, I wasn’t sure if organizing a race was the right way to take on the environmental injustice of the wood-pellet industry. I’m a runner from the Southeast, but I’m also an outsider, trying to put on an event in a state and town that I’m not from, with people who need so much more than one person can provide.

Thomas originally hails from the Southeast and has spent years running the region’s mountains and trails. Photo: Brendan Davis

My doubts mostly disappeared once the morning of the event arrived. The gathering was small, but the smiles and hugs were huge. Everyone was excited to move together. The 10-mile runners took off first, filling the road with the joyful sound of footsteps shuffling through leaf litter. Meanwhile, the 5- and 2-mile runners milled about, awaiting their start time and surveying the scene. Kids played around as adults helped pin their bibs. Dr. Krystal Martin, a local activist, passed out buttons bearing the slogan: “I want to breathe.” At 9:00 a.m. we sent the 5-mile runners off into the woods. An hour later, the 2-milers headed off on a path around the campground.

Community members cheered from the side of the road as children, parents and grandparents walked and ran together. Some of the participants were Gloster locals; some were concerned citizens who’d driven out from other parts of the Southeast simply because they wanted to learn, engage and connect. Even the shuttle bus driver, Mr. Bradley, decided to join in. This multigenerational bond is integral to the Gloster community. In the face of the hazardous air pollution caused by the pellet industry, everyone cares for everyone else.

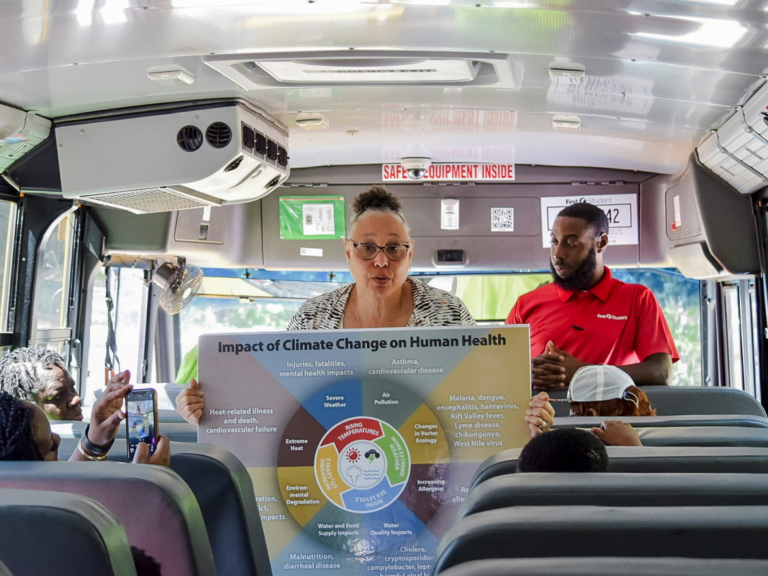

On the bus to the EARTH run, Dr. Gerri Cannon-Smith of Mississippi Health Professionals for Climate and Health Equity engages young participants in a lesson on the different stages of climate change.

Even wrong turns couldn’t sour the mood. An hour or so after start time, I learned that a couple of 5-mile runners had failed to check into the midway aid station. Both were seasoned runners, but new to trails. I took to the woods, tracing the course backwards and calling out into the wind, worried that this experience would ruin their perspective of trail running.

When I found them, both were smiling and laughing, and they eagerly recounted the experience of traversing through riverbeds, scrambling up and over logs and encountering wildlife. Their stories reminded me of my own wrong turns, and of the beauty of being lost in these places. As we ran and hiked the last 3 miles of the course together, we talked about everything from the beauty of the forest to the importance of protecting it and the need for women’s equality and leadership.

The EARTH run was never meant to be a takedown of the biomass industry. It was meant to be a source of conversation, a way for people to connect with others who they may otherwise have never known, a source of inspiration to spark deeper connections with these forests and an example of what collective action can look like.

I had spent months worrying over the event, constantly trying to explain to people how movement with others can be a spark for change—how the running community had done that for me. Hearing people get excited about discovering the forest together, and seeing the trails become a backdrop for meaningful conversation, was the truest measure of success.

Running won’t solve the complex push and pull over what constitutes sustainable industries and economies. But it is a source of empowerment and joy. And in the journey toward a clean and equitable future, that matters just as much.

Editor’s Note: Want to support Gloster, and similar communities, in the fight against the biomass industry? Head to earthgloster.com to donate and learn more.

Dr. Krystal Martin

Founder, KMartin Group

Founder, Greater Greener Gloster Project

“It’s important to be here to bring about the awareness of what’s going on in my hometown. What’s happening in our community—the health impacts that are affecting the children and the adults—deserves to be told. We need to come together in solidarity.

I’m concerned with the health issues [brought about by the wood-pellet plant]. My mom is here today, and she has been dealing with breathing issues. My son and the rest of my family lives here, and their health concerns are important to me, too. Somebody has to stand up, talk about the issues, advocate for what is happening and fight for environmental justice.

My hope for the future is that we can reduce air pollution in the community. I also hope for better health care. If we are going to have harmful plants like this, then we need to also focus on quality health care for people in rural communities.”

Kadin Love

Regional Director, JULIAN

“The issue in Gloster is a direct example of how large-scale companies prey on Black communities … The work that we’ve done is to support the community in this direct effort and access to medical care—have them do a complete medical checkup. I’m working to create a coalition of folks working on biomass pollution to spotlight areas like Gloster, to get the support that these towns couldn’t on their own.”

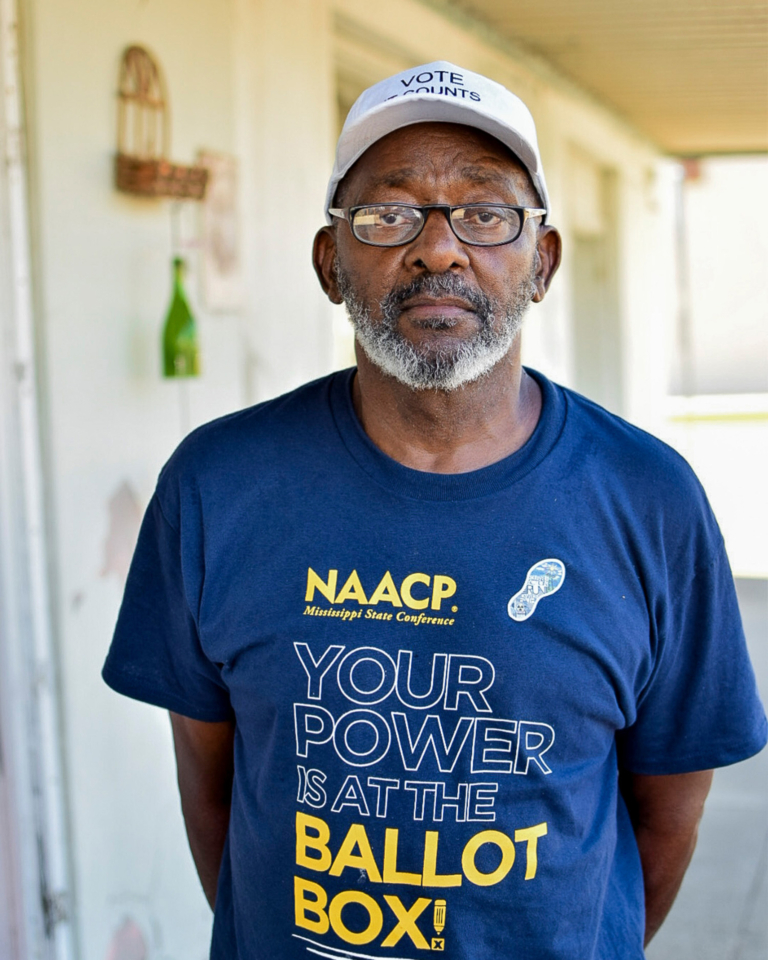

Jimmy Brown

Environmental Chair, Amite County NAACP

Member, Greater Greener Gloster Project

“We are fighting for the health of the people in Gloster, especially for the kids … I always have my mask with me now because when I stay outside in the air I get winded. It makes it hard to breathe.”

Jerry White

Former President, Amite County NAACP

“I’m here in support for the people and kids of Gloster because I don’t want to see no child poisoned by any business. I want to do all I can to help Gloster.”

Janice Lyons

President, Amite County NAACP

“I’m out here today because we do have a voice, and we want to know that the citizens of Gloster and the county have a voice, too. We are concerned about the air, and we want to make a difference. We want people to register to vote and stay connected to those that are trying to fight for them.”

Jamia Horton

Youth NAACP

“Right now, we’re young and we’re inhaling [pollutants] and in a couple more years we won’t be able to [breathe]. The kids in Gloster should know about their future. My grandma has cancer. She got it when they first started working [on the plant]. She’s recovered from it. But my dad stays one mile from the mill, and he just found out that he has prostate cancer.”

Naya Black

US Gulf South Organizer, Dogwood Alliance

“[The forests] suck up carbon dioxide naturally, and when we cut down our forests, we are taking away that defense. When we chop down trees into the small sizes … and when those emissions get released … into the air, people don’t want to breathe that.”

Jordyn McGahee

Youth NAACP

“The youth don’t know a lot about how to prevent certain things [like the presence of harmful industry]. This event is a way to educate them on what’s going on and why people are getting sick, so they know more.”

Kelvin Cotton

Community member

“I think there is a level of environmental racism going on because Gloster is predominantly Black. [EARTH run is important] because it is bringing awareness. When people see you running, they’re questioning why there’s this diverse group of people with cameras, why there’s music, why there’s a health fair … the more we do, the more people see our face, the more conversations that we have.”